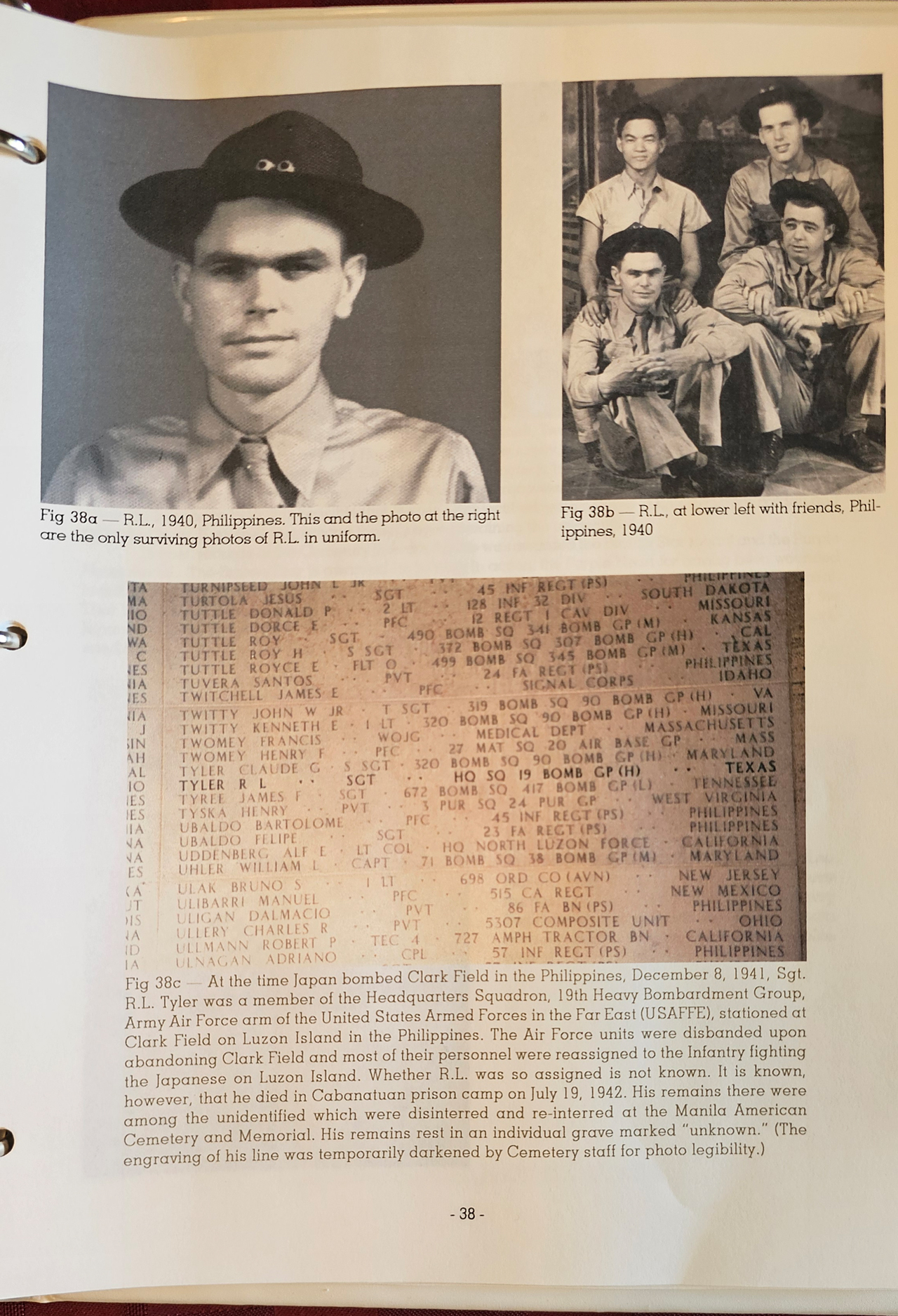

Sgt. R.L. Tyler, original image from DPAA press release. Photo restoration filter applied by LubbockLights.com

An American hero from West Texas was not destined to rest forever in “common grave 312” at Cabanatuan Camp Cemetery in the Philippines – his death certificate written in pencil by a fellow prisoner on the back of a label for Alpine-brand canned sterilized unsweetened evaporated milk.

Nor was Sgt. Robert “R.L.” Tyler of O’Donnell destined to forever remain unidentified with other Americans in the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial where his body was moved after World War II.

R.L. is coming home because the Army kept its word.

He’ll rest next to his parents who etched his name decades ago on a shared tombstone at the O’Donnell Cemetery, 40 miles south of Lubbock.

R.L.’s nephew, Jeff Tyler, described how his uncle – growing up in the 1930s – got into the Army Air Corps.

“In those days, the carnivals would come through the communities that have these barnstorming guys – the old bi-planes and do the loop-de-loops and stuff. And that just really captured his imagination,” said Jeff, who came to Lubbock this week from California to honor his uncle.

R.L. graduated from high school in the spring of 1939 without a job.

“Middle of the Depression, he decided he wanted to join the Army Air Corps. So, his dad drove him up here to Lubbock from O’Donnell, and he joined the Air Corps in November,” Jeff said.

R.L. wanted to fly but with no college education, he ended up as a radio operator assigned to the Philippines, which the Empire of Japan overtook. R.L. survived the Bataan Death March, but not malaria.

So many Americans died in the Cabanatuan POW camp that they were buried in common graves. There were efforts to recover them, according to the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA).

“Due to the circumstances of the POW deaths and burials, the extensive commingling, and the limited identification technologies of the time, all of the remains could not be individually identified,” said a DPAA press release from 2019, describing previous efforts.

For decades, that’s where it stood.

The Bataan Death March

“In 1942, Tyler was a member of Headquarters Squadron, 19th Bombardment Group, when Japanese forces invaded the Philippine Islands. Intense fighting continued until the surrender of the Bataan peninsula on April 9, 1942, and of Corregidor Island on May 6, 1942,” said a DPAA press release.

Thousands of U.S. and Filipino service members were captured and sent to POW camps, including Tyler.

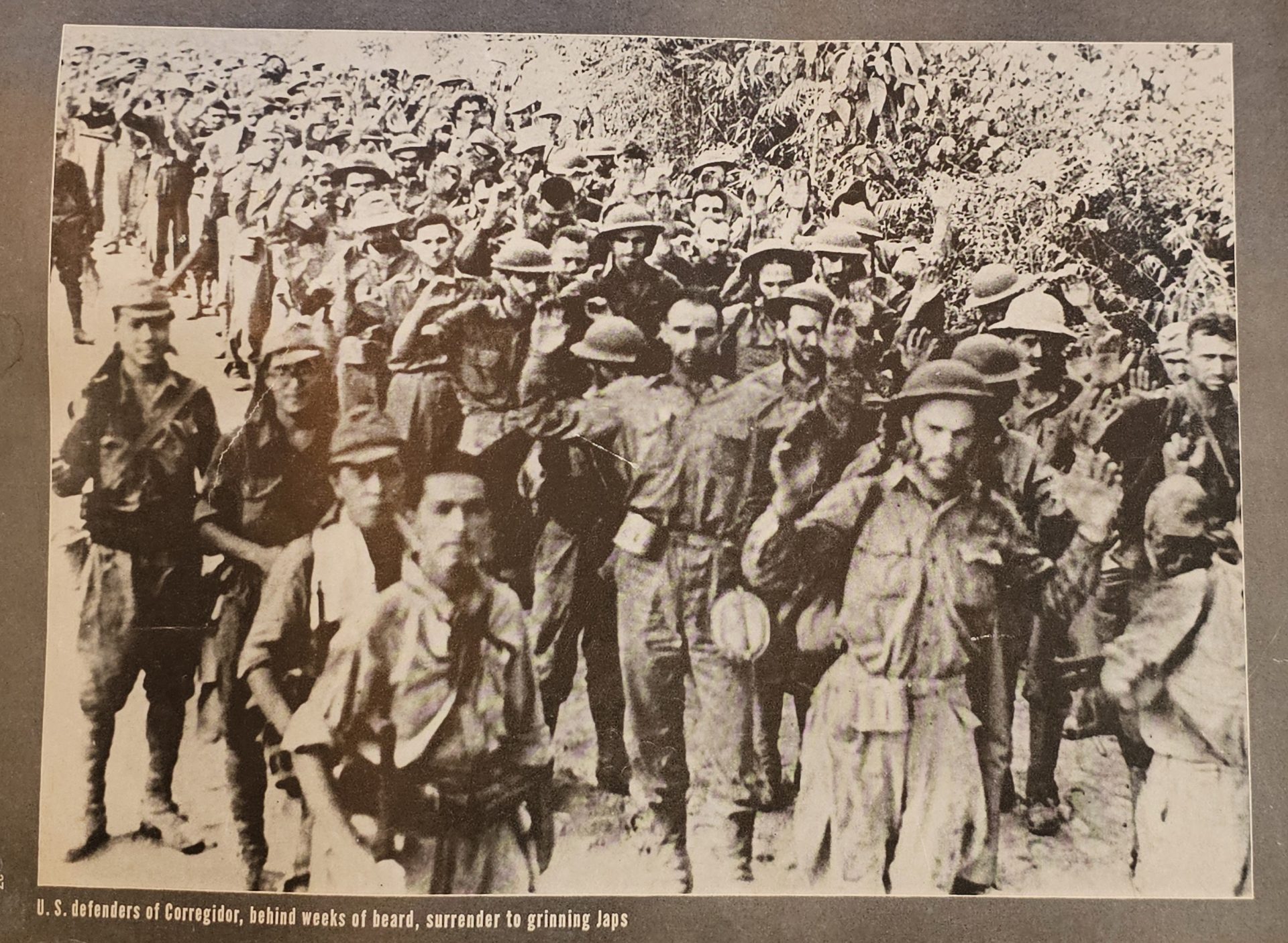

The National Museum of the United States Air Force website said, “The Bataan Death March began on April 10, 1942, when the Japanese assembled about 78,000 prisoners (12,000 U.S. and 66,000 Filipino). They began marching up the east coast of Bataan.”

They were marched 65 miles in six days.

“The men, already desperately weakened by hunger and disease, suffered unspeakably during the March. Regardless of their condition, POWs who could not continue or keep up with the pace were summarily executed. Even stopping to relieve oneself could bring death …,” the museum website said.

“Some of the guards made a sport of hurting or killing the POWs. … Some enemy soldiers savagely toyed with POWs by dragging them behind trucks with a rope around the neck. … POWs had the water in their canteens poured out onto the road or taken by the Japanese just to be cruel,” the museum said.

Death toll estimations vary wildly – up to 18,000.

The Tyler family comes to West Texas

The Tylers have links to the White House.

“I’m a fourth cousin four times removed – President John Tyler,” said Jeff Tyler of America’s 10th president who served from 1841-45.

“Granddaddy was born in Mississippi in 1884. He moved to the Fort Worth area sometime in the teens, I think, late oughts or 1910s,” Jeff said.

All five of Clinton and Edna’s children were born in the Fort Worth area, Jeff said.

“In 1927, they moved to O’Donnell and I don’t really know why. They rented various farms in the O’Donnell area and grandad never bought a place,” Jeff said.

Jeff’s dad, Truett, graduated from Texas Tech in 1949, married in 1950 and moved to Pittsburgh to work for Westinghouse. Jeff’s family then moved to California, but Truett never stopped calling O’Donnell home, Jeff said.

In 2004, Truett made an offer on a house in Wolfforth much to Jeff’s surprise. He lived there until his passing in 2017. None of the close family lives in O’Donnell or Tahoka anymore. Everyone moved away or died.

No goodbye from R.L.

Jeff relayed the story of R.L.’s enlistment in the Army Corps from his dad.

“He had come home from high school one day – that day in November expecting to see R.L. at home and he wasn’t there. So, he asked his mother, ‘Where’s R.L. and where’s dad?’ And she said dad took R.L. up to Lubbock to sign up for the Army Air Corps. And Dad kind of goes into some detail about his reaction. ‘I didn’t even get to say goodbye,’” Jeff said.

Jeff had put together some of the history through his dad’s journal writings and R.L.’s memorabilia.

“He came through Southern California in December because I have the menu for Christmas dinner that was served in March Air Force Base,” Jeff said.

“It has turkey and ham for the main dishes, several side dishes, several desserts and at the bottom it says cigarettes,” Jeff said.

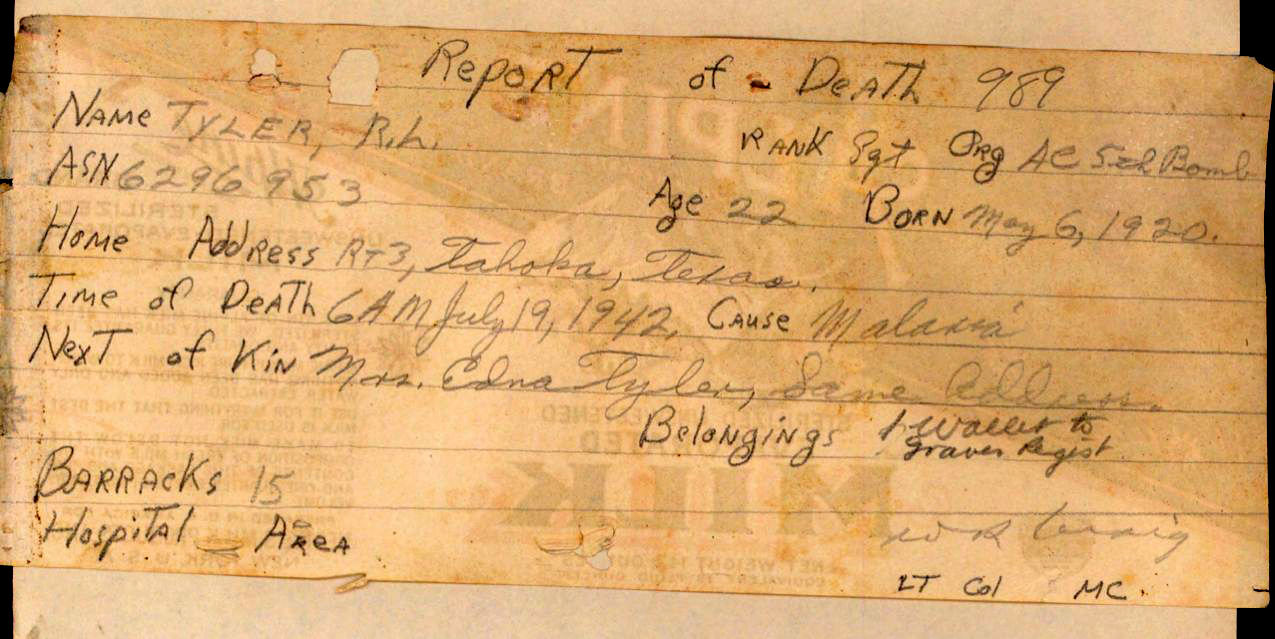

The can label used in the Philippines memorialized him for all time as death 989. He died July 1942 at 6 a.m. His only possession – “1 wallet.”

His next of kin was his mother, “Mrs. Edna Tyler same address” which was Rt. 3, Tahoka, Texas – written in cursive.

“Dad went to the Philippines in May of 2001 to basically see where his brother had been and try to retrace his steps. He walked a stretch of what is now a paved road that was part of the Bataan Death March route. He wrote up a journal with pictures called ‘My Philippine Pilgrimage,’” Jeff said.

An emotional journey

The Tyler family’s journey to bring R.L. home started in 2017 with a DPAA call to Jeff.

Jeff got Truett involved by asking for a DNA sample in May of that year – four months later Truett passed away without knowing confirmation of the results.

Truett wanted R.L. interred in the Philippines in a marked grave. Jeff was prepared to do that, but fate intervened.

There was already a grave marked for R.L. back here in West Texas. Then COVID-19 happened, along with political changes in the Philippines and the Army suggested making other arraignments.

Two years later, the duty of getting R.L. home fell to Jeff, who now lives in Whittier, outside of Los Angeles.

“In September of ‘19, I get a letter from the military saying we have identified some of your uncle’s remains. We’d like to have a couple people come by and meet with you to give you the results and some documentation,” Jeff said.

The meeting was October 12, 2019.

Part of that documentation was a letter to Jeff’s grandparents which he paraphrased as saying, “We know it’s been 4 years. We’ve been unable to identify your son’s remains with any certainty. So, we don’t even know if we have them. But rest assured that if we find them, we will let you know.”

The date of the letter was October 11, 1949.

“I looked at the date of the letter and I realized it was 70 years and one day from the date of that letter until the meeting,” Jeff said – fighting back tears.

Jeff paused to gain his composure, but he was still deeply gripped by emotion.

“The Army kept its word,” he said.

Plans change

With Manila no longer an option, Jeff made arrangements to bring R.L. home to West Texas. R.L.’s remains would come from the Philippines to Hawaii then Dallas.

“They’ll be met by an honor guard and be escorted back here to Lubbock,” Jeff said.

After a stop at Combest Family Funeral Home in Lubbock, there will finally be a graveside service near O’Donnell – 82 years after his passing.

That was the plan. Then the funeral home got a call from the O’Donnell First Baptist Church.

“They’ve heard about this. They really wanna do the memorial service at the church,” Jeff remembered hearing.

He did not want to at first.

“Gee, I don’t know. We’ve already made so many changes. … So, when my wife and I talked about it over lunch, I said, ‘You know what! We cannot not do this. We have to do this.’ So, I called them back and said, ‘We’re gonna do it.’”

‘There’s your tax dollars at work’

Jeff’s extremely grateful for the DPAA.

“People joke about a government project going sideways and not turning out right. You know, ‘Well, there’s your tax dollars at work.’ But this is one instance where the tax dollars really work,” Jeff said.

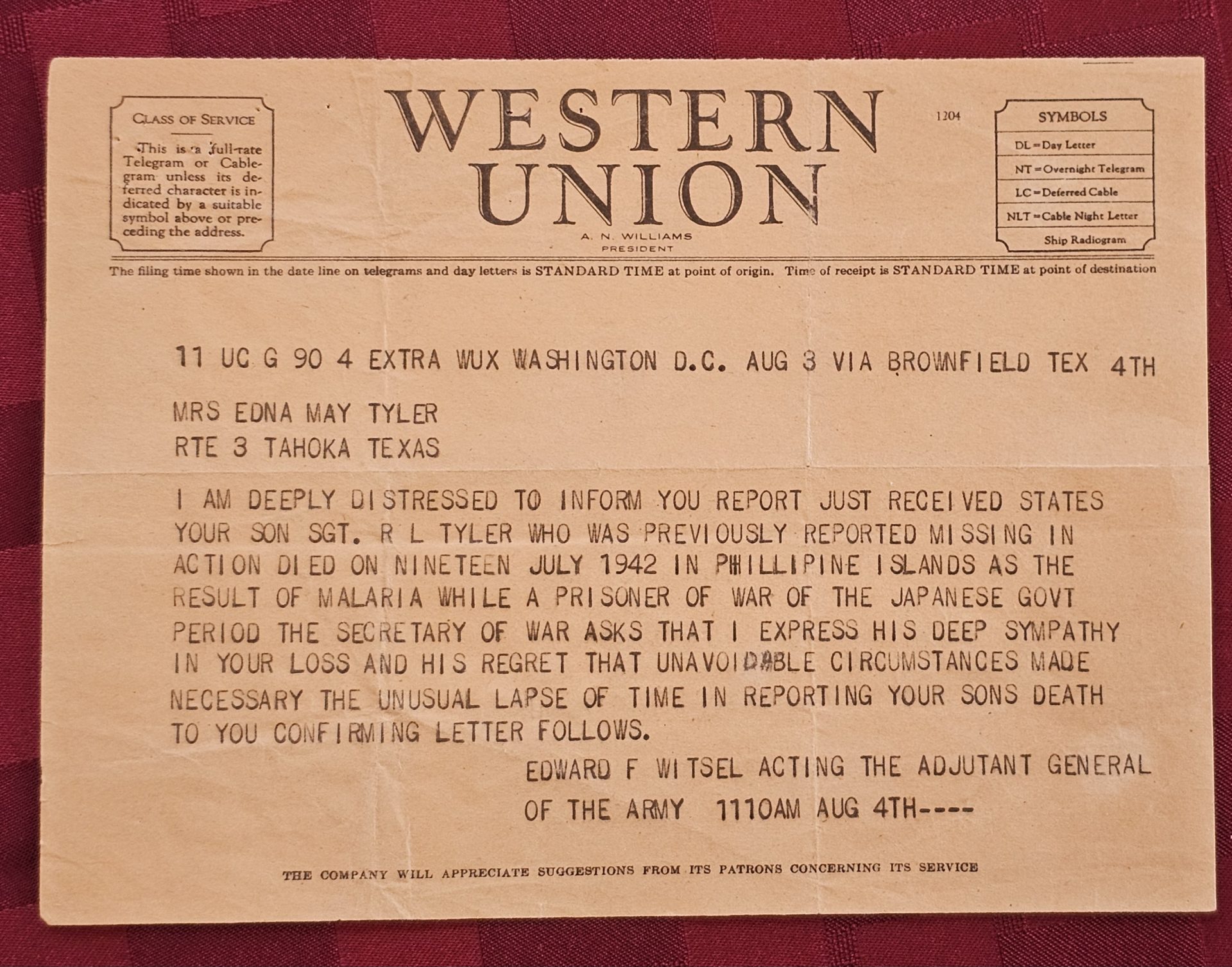

Jeff has the telegram the Army sent his grandparents dated August 3, 1942, confirming R.L.’s death, a 48-star flag presented to them and a copy of August 24, 1942, issue of Life Magazine.

In the magazine is a picture of Bataan Death March prisoners taken by a Japanese photographer. Jeff’s dad was 95 percent sure his brother was in the photo.

Please click here to support Lubbock Lights.

Comment, react or share on our Facebook post.

Facebook

Facebook