Upland Ave. near 34th St. Staff photo

Mark McBrayer took office as mayor last year willing to get rid of impact fees – one-time payments covering part of the cost of extending city services to new developments.

He’s still willing to get rid of them but not without a better option.

“I know that a lot of the builders in town don’t really like it,” McBrayer told LubbockLights.com a few days after the most recent city council meeting. “Anybody [who] wants to propose a change has to show me how it still allows the city to do what the city needs to do.”

That hasn’t happened yet, McBrayer said, but the city has a $289,000 study underway to see if adjustments are needed. The new study will consider major road projects in Lubbock, which could cause a change in the dollar value of impact fees.

“It’s one thing to hear from somebody, ‘I don’t like this.’ But it’s another thing to hear from them, ‘Here’s how I would address that issue.’ … At the moment the impact fees are what they are until somebody comes forward with a better alternative,” McBrayer said.

Developers and builders pay the fees – 25 percent of road costs. The city charges zero percent for water and wastewater.

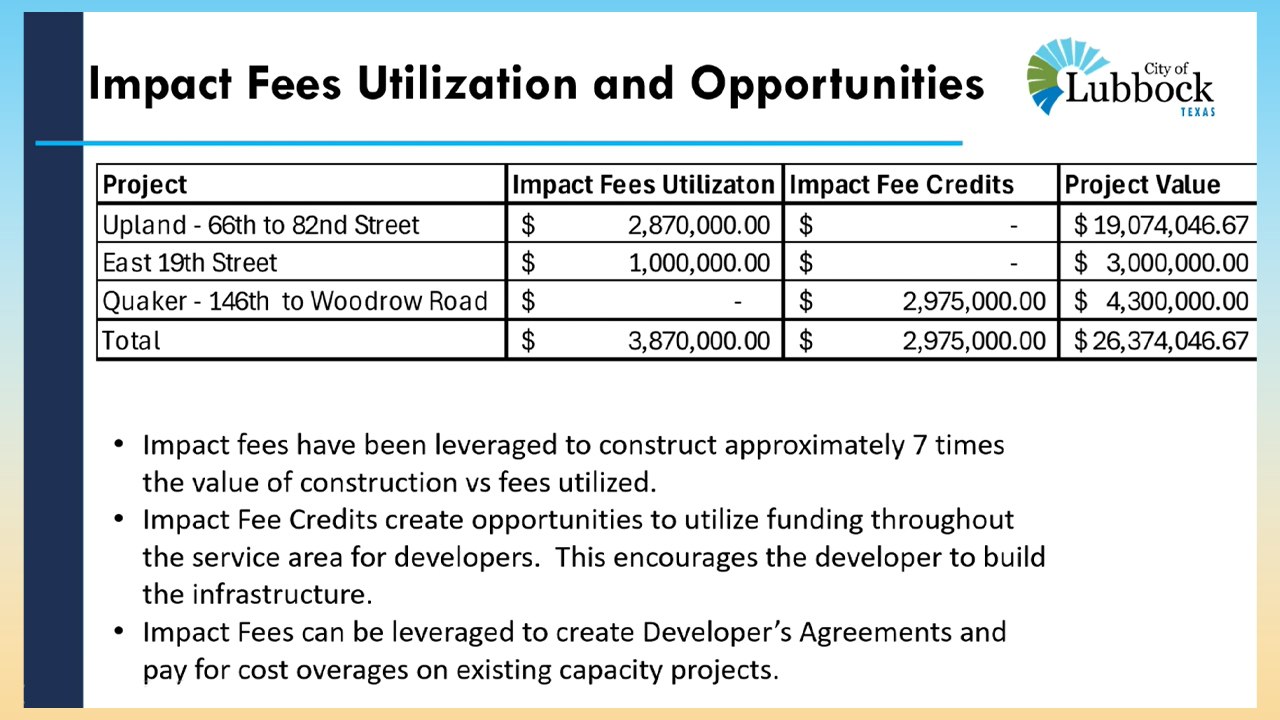

Lubbock implemented the idea in 2021 and has raised $10.8 million. The city drew down $3.9 million of that money to get $26 million of road projects underway. We’ll explain below how that works.

“It’s an effective tool at the moment, even though some people don’t like how it operates,” McBrayer said.

But Lubbock Compact thinks the city should charge more for impact fees, according to Joshua Shankles, the group’s president.

“We want maximum impact fees,” Shankles said concerning three areas in West and Southwest Lubbock.

State law allows up to 50 percent – not just 25. The city can charge specific areas differently. Shankles said it’s not to stop new growth – quite the opposite.

“We need more retail. We want more residents. That’s all fine. Developers can make as much money off that as they want. In fact, I would love it if they got filthy stinking rich off it so that they could do it some more,” Shankles said.

But if the city is paying for the new roads, it takes money away from repairs and maintenance in other parts of town. Shankles wants the people in new developments to pay more for the new growth.

The kind of changes Shankles suggested are not on the table.

But the issue is coming up for review in front of the city council.

Explaining how this works

McBrayer asked for an update on impact fees in the most recent city council meeting. John Turpin, city engineer, and Jarrett Atkinson, city manager, gave the presentation.

Impact fees paid for a portion of East 19th Street near the East Loop and a portion of Upland Avenue between 66th and 82nd streets.

A developer’s agreement – a different approach than direct impact fees – got construction started on Quaker Avenue between 146th and Woodrow Road. The developer spent his own money for 70 percent of that road and the city gave him credit as though he paid that same amount in impact fees.

Turpin said, “We’ve been able to leverage impact fees to gain basically seven times construction costs versus impact fees.”

How did Lubbock get $7 of road for every $1 of impact fee?

Atkinson used the Upland project to explain. Federal money – which is use-it-or-lose-it – was set aside, but Upland still needed a local match. Then, the cost went up. Lubbock – not the feds – pay the price hike.

“We called it the couch cushion project,” Atkinson said.

Just like people might look under the couch cushion for loose change, the city was looking for a way to cover the unexpected price hike.

It was a $19 million project and the city was going to be nearly $3 million short. It came from impact fees.

“Rather than either not getting to do it or having to come entirely out of your general fund reserves, it [impact fee money] became leverage,” Atkinson said.

Construction is underway. Upland from 66th to 82nd should be done by late summer.

Same thing on East 19th Street. The Lubbock Economic Development Alliance and Lubbock County teamed up for $2 million. But the cost was $3 million. Impact fees filled in the gap.

“Neither of those projects had to touch the general fund because you had those impact fees available,” Atkinson said.

Potential roads are identified when an area is added to the plat map. The city estimates the cost of big thoroughfare projects (not residential streets) in a 10-year plan. Then the city assesses 25 percent of that cost to the developers as impact fees which are due when construction permits are approved.

Setting limits

There are some limits.

Turpin said, “You cannot collect against existing businesses or homes.”

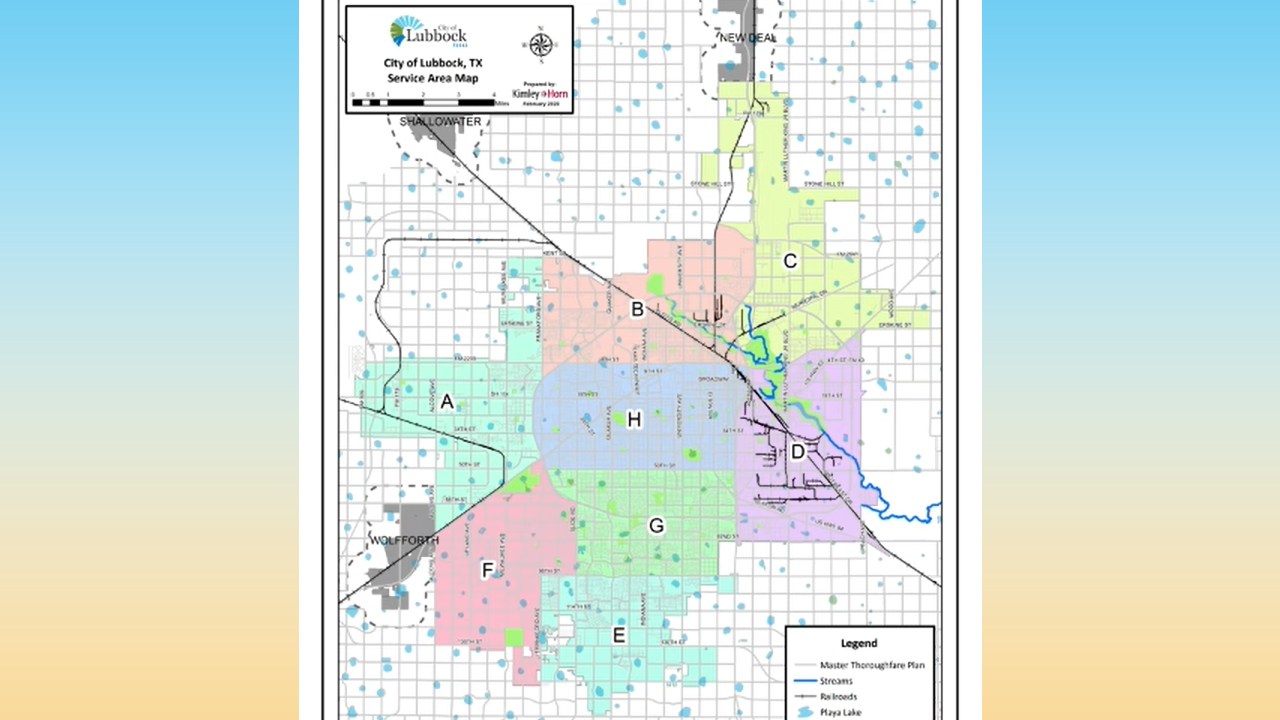

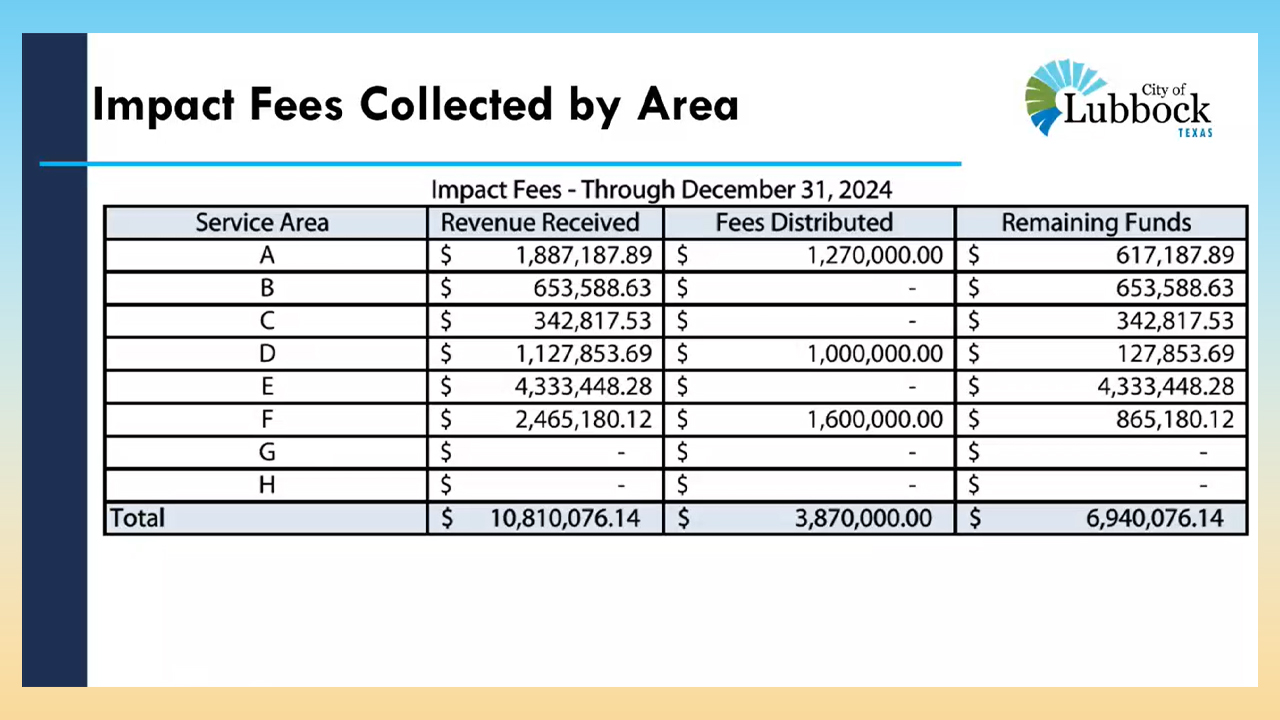

It’s for new development only and for increasing the traffic capacity – not road repairs or maintenance. The city is split into eight areas. Impact fees collected in an area must be used in the same area.

(The rules are different for water and wastewater, but those fees are currently set to zero.)

Far South Lubbock has the most money available – more than $4.3 million.

“We have some potential identified projects actually coming up,” Turpin said.

Two areas of town in Central and Southcentral Lubbock have not collected any money. But there is an indirect benefit.

You pay so I don’t

Shankles said, “The city generally does a very good job of ‘staying on top of things.’ They do as best they can.”

But if the city had to pay 100 percent for new Southwest Lubbock road development out of the general fund, it’s harder to find money for maintenance in Central Lubbock.

“You’re basically looking at like rebalancing the books in a fair way that’s more predictable. … The savings in the general fund can be allotted to any number of things,” Shankles said.

Tim Collins, councilman for District 6, shared a similar sentiment in the council meeting.

“We inside the loop – we do still pay a burden to some of that new development. But [developers] pay a greater share through this process. It allows us to grow our city and … it allows us to keep our tax rates low inside the Loop,” Collins said.

Shankles added, “We want to do two things with impact fees. We want to slow the sprawl of the city, and we want to free up funds derived from the tax monies of ‘old Lubbock’ for projects in ‘old Lubbock.’”

“I don’t mean it with any sort of malice. … But the sprawl has its own problems,” Shankles said – pointing to increased police and fire response times if they have to travel further.

There’s not only an up-front debt for building a major road, often in a bond election, but Shankles said there’s a second hidden debt, which is the need to set aside money for repair or replacement over the life of the road.

“We have to pay to service this in perpetuity, or we have to decommission it, or we have to let it fall into disrepair. … Even the newer parts of the city towards the south and southwest are going to be experiencing the same kind of problems that the older part of the city is. It’s only a matter of time.” Shankles said.

The same idea holds true for water and wastewater pipes, which is why Shankles thinks the impact fee system should be expanded. However, there is no plan to go beyond roads.

Clarification: This story was updated to put a quote from Joshua Shankles into a clearer context.

Please click here to support Lubbock Lights.

Comment, react or share on our Facebook post.

Facebook

Facebook