Carl Tepper wants to crack down on local governments using certificates of obligation (CO) for borrowing money and increasing debt.

LubbockLights.com asked Tepper, state representative from Lubbock, if he had statistics illustrating why he created legislation to limit CO use, which does not have to be approved by local voters, unlike a general obligation bond.

“Let me see,” Tepper said – followed a moment later by the words, “Holy mackerel!” Tepper said he knew the number was high, but didn’t seem to realize it nearly doubled.

As state officials work to drop property tax rates, local governments might be forced to get voters’ permission more often for new debts.

Tepper, though, has made adjustments to his legislation after hearing from local officials.

Randy Criswell, city manager of Wolfforth, said, “I can tell you I am far less concerned about this bill today than I would have been two weeks ago because I do believe that Mr. Tepper is listening to the concerns … being expressed.”

But another local official – James Fisher, Levelland city manager – thinks the legislation is not needed.

“Allow communities to manage themselves. Democracy is best at the doorstep. Local communities know what is needed within their community,” said Fisher.

Tepper said, “Cities and counties continue to, I believe, misuse the financial vehicle.”

Fisher also said, “I think you can find anybody in any walk of life to try to skirt an issue if they possibly can. But that doesn’t mean that you kill a gnat with a sledgehammer. … I’m sure there are cities out there that have done some things that they probably shouldn’t have done.”

By the numbers:

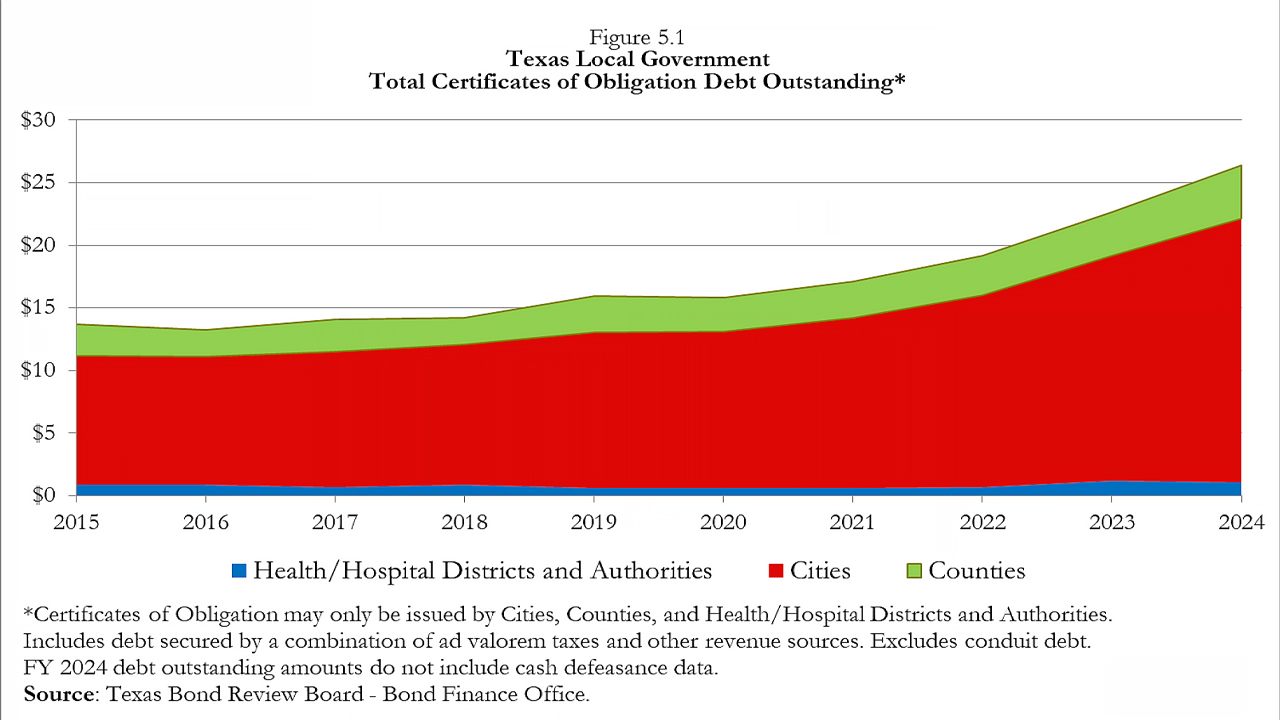

- Total CO debt in the last ten years went from $13.66 billion to $26.41 billion, according to a state report.

- Cities rack up nearly 80 percent of CO debt with counties and hospital districts accounting for the rest. Cities also accounted for nearly all the increase.

- At the end of the fiscal year in 2024, Texas local governments had $333.32 billion in outstanding debt, an increase of $81.45 billion (32.6 percent) over the past five fiscal years.

Criswell said there are reasons to leave COs alone.

“We must have that tool in our toolbox. No form of government can effectively survive if everything must be voted on by the public,” Criswell said.

Tepper said, “I think we’ve responded with some thoughtful carve-outs.”

By carve-outs, he means a longer list of exceptions (see below). And cities can still go to a public vote for debt – like always – if the bill passes.

Certificates of Obligation in Texas

COs were first authorized by the Certificate of Obligation Act of 1971. They are usually tax supported debt to pay for public works (including the materials, supplies, equipment, machinery, buildings, land, and right-of-way; and professional services).

They can also be paid back from revenue such as water and sewer bills. A CO does not require voter approval unless there’s a valid petition – 5 percent of the voters – in opposition.

The law was reformed over the years:

- 2015 reform, a CO may not be issued if the voters rejected a proposition for the same purpose in the preceding 3 years

- 2019 reform added additional requirements for publishing notice before a CO. Only counties, cities and hospital districts were authorized to issue COs.

- 2023, added limitations to the purpose of a CO.

The original bill and the adjustments

Tepper’s bill (HB 1453) wouldn’t stop COs but limit them to specific circumstances.

Originally, Tepper proposed no more COs for hospital districts – and he thinks the provision might stay. Also originally in his bill, cities and counties could still use a CO for projects that:

- Are required by law (or fix a violation of law)

- Comply with a court order

- Or respond to an emergency or disaster

The limits will change when the bill goes through a House committee and a public hearing. When the changes are made, the exceptions will also include:

- Water systems

- Drainage projects

- Landfills

- Emergency services – police and fire stations

- First responder training facilities.

- A new road, library, city hall, county courthouse, annex building and other such projects will need voter-approval if Tepper’s bill passes – even after he makes adjustments.

Stadiums, arenas and civic centers were already moved off the list in the last legislative session. Those items need voter approval.

Under current Texas law, a signature petition of 5 percent of registered voters can stop a CO and force a public election. Tepper’s bill lowers it to 2 percent.

Hospital districts – especially the one in El Paso – want to continue using COs,

Tepper said, but he’s not convinced.

“They can buy all these things that they want to. They just have to go through the voters first,” Tepper said.

Philosophical approach

Tepper is pretty sure his bill will pass, but added, “I also anticipate it’s going to be very controversial.”

Texas cities issued more than $4 billion of new debt with COs last year – the most recent year for statistics. The trend was relatively flat from 2015 through 2020 – then rising dramatically since then, according to the Texas Bond Review Board’s 2024 local government report.

Lubbock – the tenth-largest city in Texas – ranked 18th highest on the list in that report with almost $318 million owed in COs. Denton – the state’s 20th largest city – has the highest at $883 million.

Related story: Why has Lubbock’s debt neared $1.8 billion? We explain the why and how in detail

“A massive amount of debt is being taken on by local municipal, county [and] some hospital districts, in bonds – debt that will long outlast the life of the political life of the politicians who passed the bonds. … I believe that these types of debt should go to the voters first,” Tepper said.

Fisher sees it differently for Levelland.

“I will tell you it’s frustrating. Every community is different. Every community has needs. Trying to create just a blanket policy out there is just unfair,” Fisher said.

Levelland needed to borrow recently for a $6 million water meter project, Fisher said. If changes are made to the bill, Levelland could still use a CO for such a project.

The issue is broader, Fisher said.

“If the citizens don’t like it – they don’t like what their city council is doing, they can vote them out of office. They can run for office; they can get involved. Local control is always best,” Fisher said.

Criswell – as much as he appreciates changes to the bill – would like COs to still be an option for roads. He mentioned Alcove Avenue – part of which is inside Wolfforth.

“We’re looking at all options that we can. But if the option for the construction of Alcove becomes debt by the City of Wolfforth, then certificates of obligation are going to be needed to do that,” Criswell said.

“I do not believe that major debt needs to come back to the voters in every circumstance,” Criswell added.

However, some things need a public vote in Criswell’s opinion.

“Say we were looking at building a water park in Wolfforth. … That should be a proposition taken to the voters” Criswell said, adding the same goes for a golf course or a library.

Property tax drives the discussion

Tepper and Fisher both said property taxes are the motivation for change. Schools have usually been the focus of recent reform, but this time Tepper turned his sights on other local governments.

Fisher said, “Your hands start getting tied because they’re trying to drive property taxes down without realizing everything that goes into managing and providing for your community.”

Tepper said, “When you take out these bonds, you’re indebting the voters and the property taxpayer. And I think that they should have more of a say.”

Several sources including Texas Tax Protest – a business with offices in four major cities – said Texas has among the highest property taxes in the nation.

“The average effective property tax rate in Texas is approximately 1.8 percent, making it one of the highest in the nation. This means that for every $100,000 of assessed property value, the average annual tax bill is around $1,800,” the business website said.

The amount varies across Texas depending on location. Different sources cited different numbers on the average tax burden.

For example, Rocket Mortgage, citing numbers from 2022, said the number was 1.68 percent – the sixth highest in the nation.

In 2023, the legislature approved $12.7 billion over two years for property tax relief. The state took on 10.7 cents per $100 valuation of school taxes.

Another round of property tax relief will cost the state another $1 billion or more (over two years) according to official documents although media reports have put the amount up to $3 billion.

Please click here to support Lubbock Lights.

Comment, react or share on our Facebook post.

Facebook

Facebook