(Image: Fred Gray honored by Texas Tech)

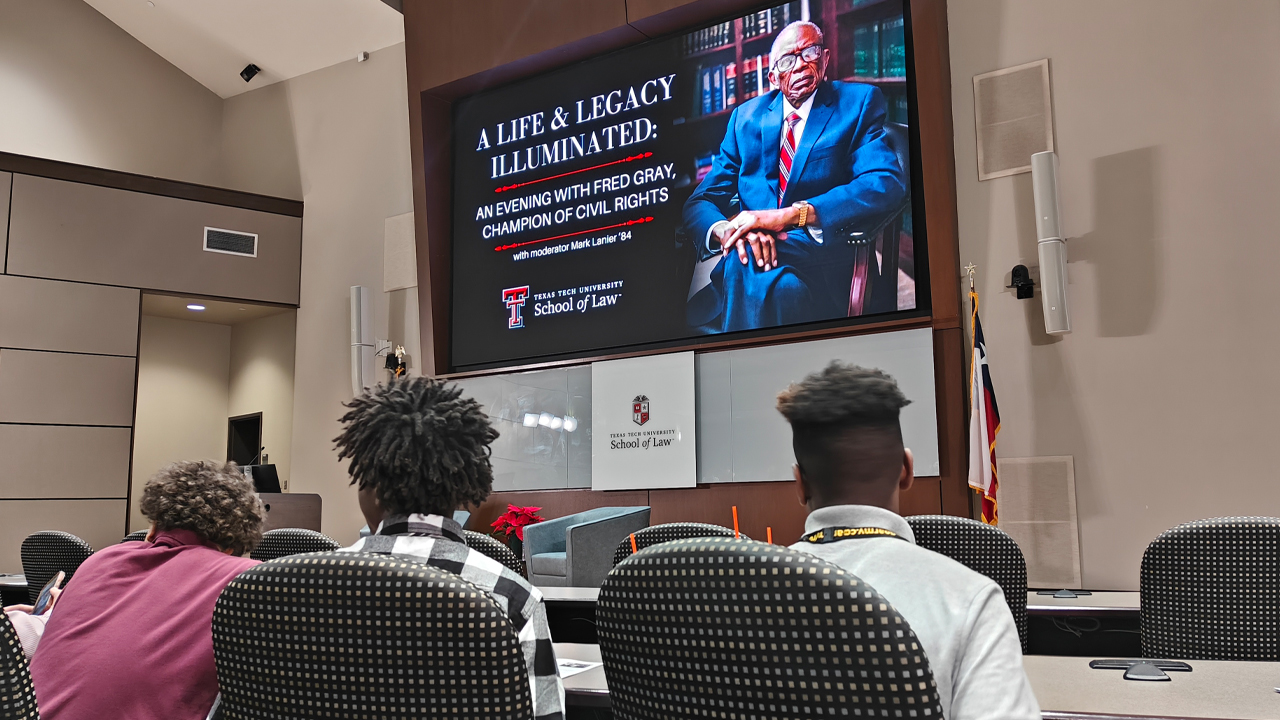

Two weeks before his 93rd birthday – and decades after representing civil rights heroes Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr. – Fred Gray stood before a crowded Lanier Auditorium inside the Texas Tech University School of Law.

He told the crowd to keep going – to set the record straight – and do it non-violently until justice rolls down like water, and righteousness like a mighty stream.

Gray had just been awarded an honorary degree from Texas Tech and the school announced the Fred Gray Endowed Chair in Civil Rights and Constitutional Law.

Mark Lanier, Lubbock native, nationally known lawyer and Tech graduate, made the evening possible – donating $1 million to Tech for the endowed chair and approaching Gray about naming it in honor of his lifetime of civil rights work.

Lanier also moderated an hour-long discussion with Gray detailing his unlikely rise as an African-American man in the segregated south to become the attorney for Parks, King, students who forced the desegregation of Auburn University, victims of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study and Claudette Colvin – who laid the path for Parks’ famous refusal to give up her bus seat.

Lanier also turned Gray into a Texas Tech fan – more about that in a bit.

The crowd lauded Gray Thursday evening with numerous standing ovations – a crowd including law students, many local officials, a choir from St. John Baptist Church and five Dunbar Middle School students whose teacher brought them to see the man described by Tech as a “champion of civil rights.”

Lawrence Schovanec, Tech president, spoke briefly before Gray’s speech, saying, “We gather here tonight to celebrate progress and the man whose work epitomizes the very essence of justice and progress.”

Gray’s commitment to civil rights and his dedication to justice and equality serve as a guiding light for all, Schovanec said.

Gray had to leave the south to become an attorney

Fred David Gray was born in 1930 in Montgomery, Alabama. He originally went to school at the Nashville Christian Institute to become a preacher. He was encouraged to study law and since law schools in Alabama would not accept African-American students, he earned a degree from Case Western Reserve University in Ohio in 1954.

Returning to Montgomery, he started practicing law. At the same time, Claudette was a 15-year-old student at Booker T. Washington High School. School let out early one day in March 1955. In those days, African-American passengers rode in the back of the bus.

As Gray told the story, white passengers got on the bus at a time when students would not normally be on board. Dealing with an unusually crowded bus, the driver asked Claudette to move. Two of her friends did move. Claudette did not.

She was already seated in the back section, Gray said. But the driver wanted her to move even further back. A police officer arrested her for delinquency.

Gray was her attorney. He pointed out to the judge that Claudette was already in the back of the bus. It didn’t matter. She was convicted and sentenced to unsupervised probation.

“She was disappointed because she thought she had not broken any law,” Gray said.

Gray met with city officials and the bus company.

“They were all sorry about what happened to Claudette and said it won’t happen again,” Gray said.

But on December 1, 1955, it happened again. This time it was Parks and the historic case leading to a successful Montgomery bus boycott. Parks worked only a few blocks from Gray’s office and they often had lunch together. Gray was her lawyer too.

Gray met King in the process of planning a boycott. They continued to be friends over the years.

On March 7, 1965, protesters planned a march from Selma, Alabama, to the state capital to protest voter suppression. They were beaten back by state troopers.

Two days later, King led even more protesters to the Edmund Pettus Bridge with state troopers not too far away. On the bridge, King led a prayer and turned the protesters around. According to history.com, some called King a coward. But Gray told the full story at Tech.

Gray filed a federal lawsuit before that incident to get a court-ordered guarantee state officials would not use violence. A federal judge called him in.

“When a judge, a federal judge particularly, calls you, you’re in trouble!” Gray declared with special emphasis on the word trouble.

It was trouble. The judge ordered Gray to stop the protesters from marching.

“He said, ‘Attorney Gray. You’re an officer of the court! Confer with your clients.’”

Gray thought there was a chance, if he played by the judge’s rules, he could get federal protection for the marchers.

“I had my work cut out for me,” Gray said. The civil rights movement was in full swing by this time. He had to persuade King and the others to hold off. But they were fighting for their rights, Gray said. He drove from Montgomery to Selma and went straight to King.

“I didn’t call him Dr. King. I called him Martin. He called me Fred,” Gray said.

“This case will probably be the most important for all of us. I need your assurance,” Gray told King

Gray explained he needed the march to not go forward until a federal judge was ready to hold a hearing on the case.

“Fred, I understand. You have my word,” Gray said King told him.

The march ended in prayer and did not go to Montgomery – at least not that day. Later, that same federal judge gave an order to protect the protesters and the march happened – just not as quickly as originally planned.

Gray accepts honor but not for himself

With several stories just like the Selma march, Gray described a career of milestone after milestone of systematically destroying segregation.

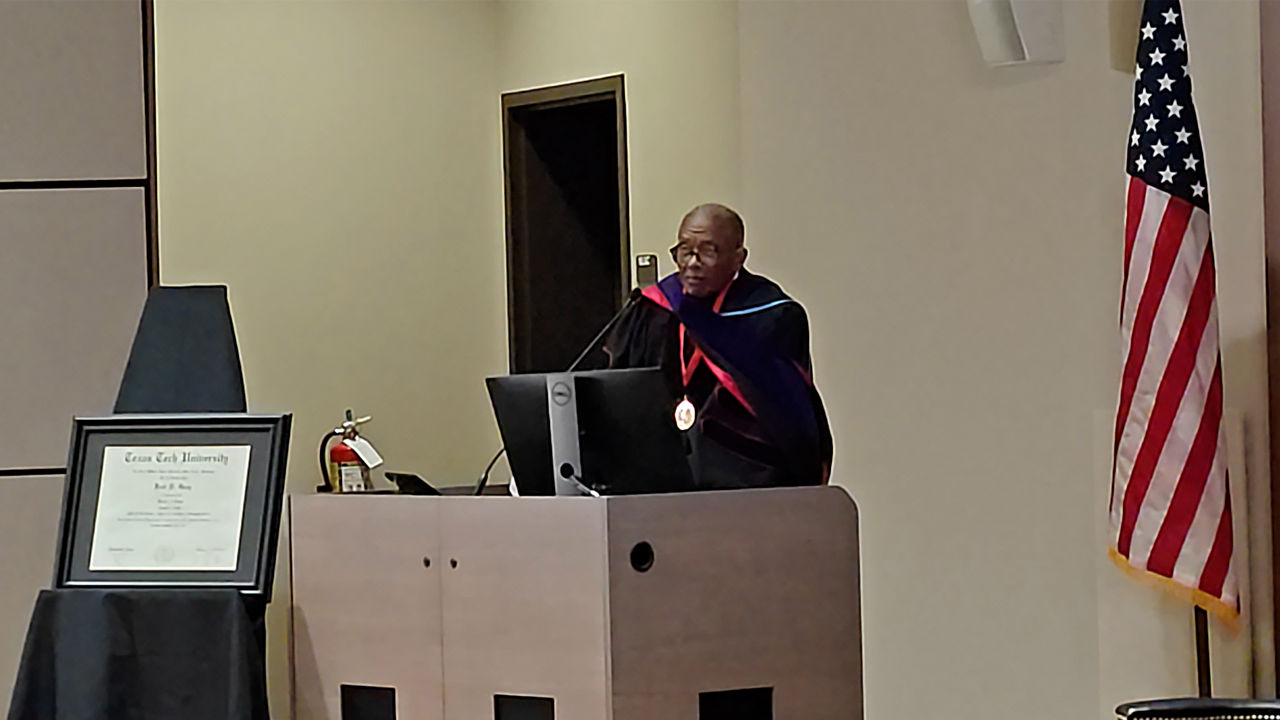

“My only concern then was to obtain for African-Americans all of the rights and privileges that they were entitled to under the Constitution and laws of the United States of America,” Gray said while wearing Texas Tech graduation regalia. “My commitment was to destroy everything segregated I could find. And that’s what I have done for the last 69 years.”

“I never thought about receiving any type of honor, but I’m appreciative of this award and this degree, because it has special meaning to me,” he further explained.

“I particularly accept it on behalf of – and I already told you about – Claudette,” Gray said. He also mentioned 623 men who were denied treatment as part of a syphilis study. The case resulted in a $10 million settlement.

“I accept it on behalf of all those unknown heroes and clients whose names never appear in print media – whose faces never appear on television,” Gray said. “They are the persons who laid the foundation so that you can honor me here this evening. I accept this award on their behalf.”

“I found racial discrimination in almost every aspect of American life. I never dreamed that years later I would receive such a prestigious award from this or any other institution,” Gray said.

Now a Tech fan

When Lanier asked if Gray would like to be honored by Texas Tech, he made a Red Raider fan.

“He thought about it, and he said okay. And then he rapidly became the biggest Texas Tech fan,” Lanier said.

“And I cannot tell you how many Saturdays my cell phone rings, and I look, and it’s Fred Gray, and, ‘Are you watching the game?’”

“Look, we’re gonna win this one. I feel good about it,” Lanier quoted Gray as though he were reenacting a phone call during a televised football game. “But he’s calling me because he’s a fan now.”

“He did not call me on the Texas game,” Lanier said to the amusement of the crowd.

But the fandom goes beyond football. Gray, in his speech, said Texas Tech is one of the best law schools in the country.

“Give yourselves a hand,” Gray said, saying he met some of the law school students.

“I’m greatly impressed by them.”

For Lubbock, ‘a big deal’

Naomi Doss was among the choir singers who performed “We Shall Overcome,” and “Lord, You’re Worthy.”

“For Lubbock, this is a big deal. To honor someone who’s really great – it’s a privilege to be here,” she said.

She thinks the nation is still weak on race relations and acknowledges the older generation knows much more about Rosa Parks than younger people.

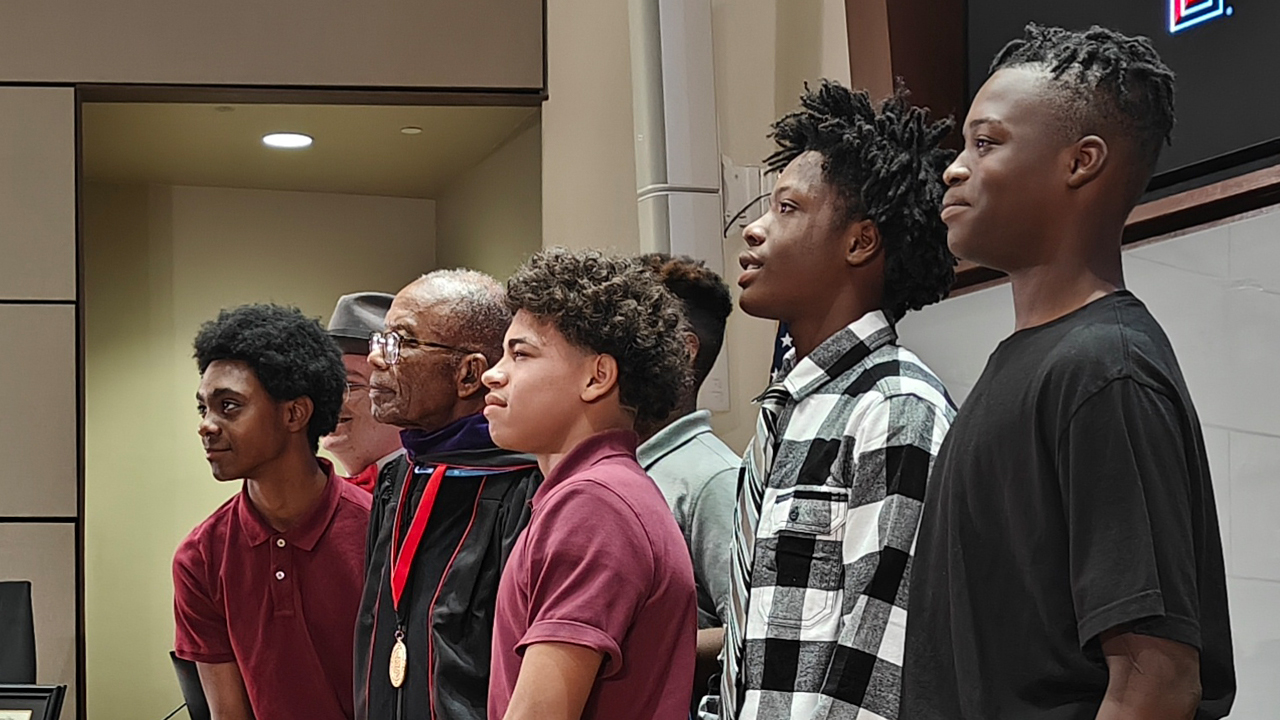

Curtis Jackson, an 8th grader, said, “It was like a learning experience for me, because I want to be a lawyer when I grow up.”

Curtis was impressed by the story of Claudette.

His fellow 8th grader, Jonathan Burns, said, “He showed me that I can do amazing things too.”

Both young men think things are better now, thanks in part to Gray’s hard work. And they both think there’s still some unfairness. Gray said the same thing.

‘Brother, keep pushing’

“The struggle for equal justice continues. This country has two major problems still remaining: racism and inequality. And they are wrong,” Gray said.

Days before Congressman and civil rights legend John Lewis died in 2020, Gray visited with him. Lewis was on the bridge for that famous 1965 prayer.

“I asked the congressman, considering his great civil rights records, what he wanted me to do,” Gray recalled. “He said, ‘Brother, keep pushing. Keep going. Set the record straight.’”

“So, I say to all of you – and all of us – and all the persons who are interested in civil rights – keep pushing,” he said.

Facebook

Facebook