Prairie Dog Town in Lubbock

Lubbock has a conflicted relationship with prairie dogs.

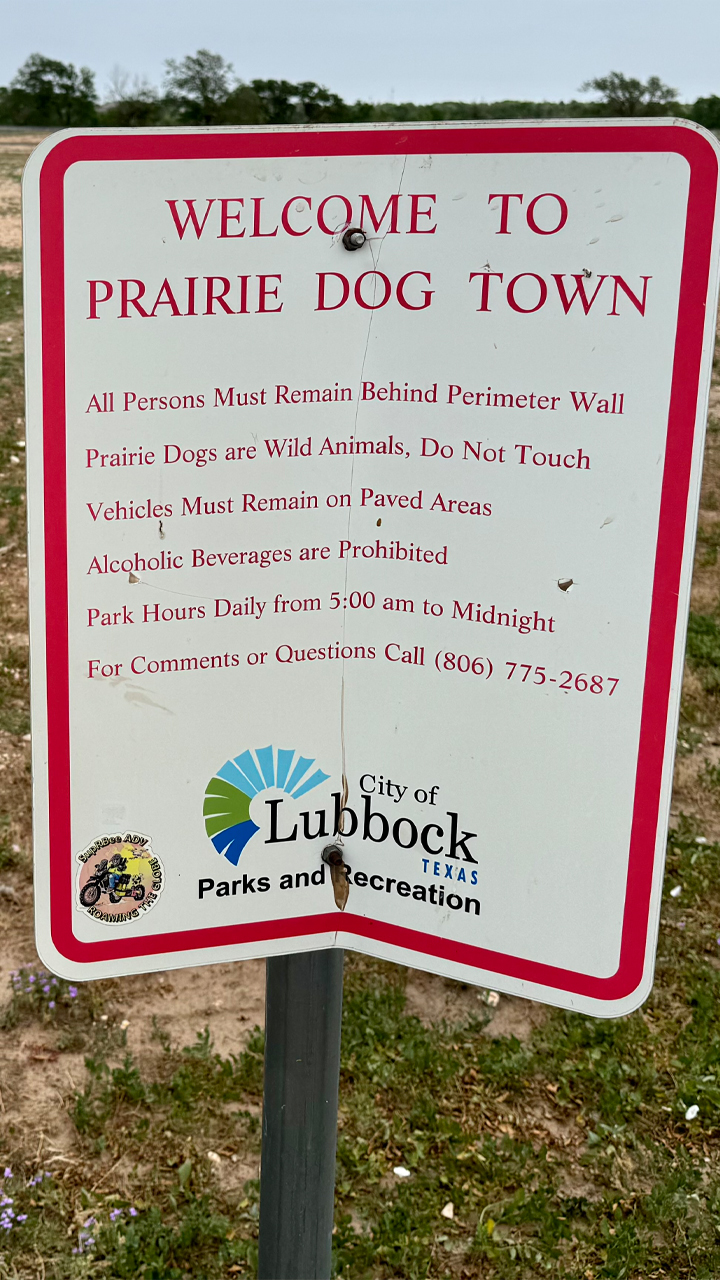

The city celebrates the cute, furry critters on its website and for almost 90 years at the city’s popular Prairie Dog Town in Mackenzie Park.

The city also kills prairie dogs because holes in parks leading into their byzantine burrows are a safety hazard. The city has not been sued for prairie dogs, but aerial images provided by the city showed park after park where green grass gave way to bare dirt and countless holes.

Efforts are made to relocate prairie dogs, but only a few people can do it.

“There are removal techniques, but given the extreme numbers, this is not a viable option,” said Lacey Nobles, spokesperson for the city.

“The overpopulation of the black-tailed prairie dogs far exceeds the amount that could reasonably be relocated. We also have no options regarding where to relocate them. In short, the population is out of control,” Nobles said.

Michele Natalino, who has 15 pet prairie dogs in her Lubbock apartment, said “People either love them or they hate them.”

The city gets stuck between the lovers and the haters.

“I see both sides of the argument,” said Brooke Witcher, assistant city manager.

‘They’re ready to get rid of them’

Some people who hate prairie dogs call Micheal Askew.

“The customers that we run into are just fed up,” said Askew, the director of Lubbock’s Bug Tech, adding they just want the little tunnel diggers dead.

“They are very destructive when it comes to yards. They try to deal with the prairie dogs for a little bit. But once it gets too destructive, they’re just ready to get rid of them,” Askew said.

An airport project in the Texas Panhandle earned Bug Tech $100,000, he said. Prairie dogs by themselves are no problem for airplanes. But they attract birds of prey and bird strikes can be deadly for passenger planes.

Bug Tech can use bait, depending on the time of year, a so-called sulfur bomb, or a machine that pumps carbon monoxide into a burrow to kill them.

‘You’ve moved into their yard’

Gena Seaberg visits Lubbock often from her home in Washington state, where she’s a prairie dog advocate.

“I do like to acknowledge the side that doesn’t care for them because I understand they can be seen as a nuisance. But again, if we can get the world to understand that you’ve moved into their yard and they’re just doing their best to survive,” Seaberg told LubbockLights.com.

Lubbock’s growth will continue to exacerbate the situation.

“The prairie dogs have been pushed from their habitat and it’s a daily occurrence. You see it all over town with development,” said Glenda Kelly, president of the Llano Estacado Audubon Society.

Advocates say prairie dogs are vital for the local ecosystem – impacting 140 or more species of plants and animals (more on that below).

Prairie dogs and American exceptionalism

Virginia Whealton, Ph.D., an assistant professor at Texas Tech University, teaches history.

“I would say that they are an early proof of American exceptionalism,” she said.

President Thomas Jefferson got into a spat with at least one European philosopher who believed plants and animals on the American continent were inferior because there was something “fundamentally wrong” with America’s climate, Whealton said.

The Lewis and Clark expedition gave Jefferson just the rebuke of European intellectuals he was looking for.

“They spend an entire day capturing a prairie dog which they sent to Thomas Jefferson – a live prairie dog. It runs around Monticello and Thomas Jefferson is absolutely delighted with it,” Whealton said.

“Then the prairie dog goes and lives at the first big American museum up in Philadelphia, where the museum keeper there talks about how the prairie dog is a ‘pleasing little animal,’” Whealton said.

In the early 1800s the prairie dog is among this wealth of species Europeans know nothing about.

More than that, the prairies of middle America were seen as worthless wastelands. And here were these industrious little creatures that found a way to conquer them and make them home.

“The prairie dog embodies the exact virtues that they want for the nation,” Whealton said.

Americans were not sure how the burrowing owls fit in, but one idea was prairie dogs were acting as gracious hosts to the owls. They were seen as noble, well-governed, orderly and performing duties to each other. This continued in the days leading up to the American Civil War.

“They were seeing hope during times of political strife, and I think that’s pretty remarkable,” Whealton said. “The prairie dog was important to the formation of American national identity in the early 19th century.”

Lubbock’s world-famous history

“Of all nature’s wild creatures, none is more appealing and entertaining to watch than the prairie dog,” the city’s website says.

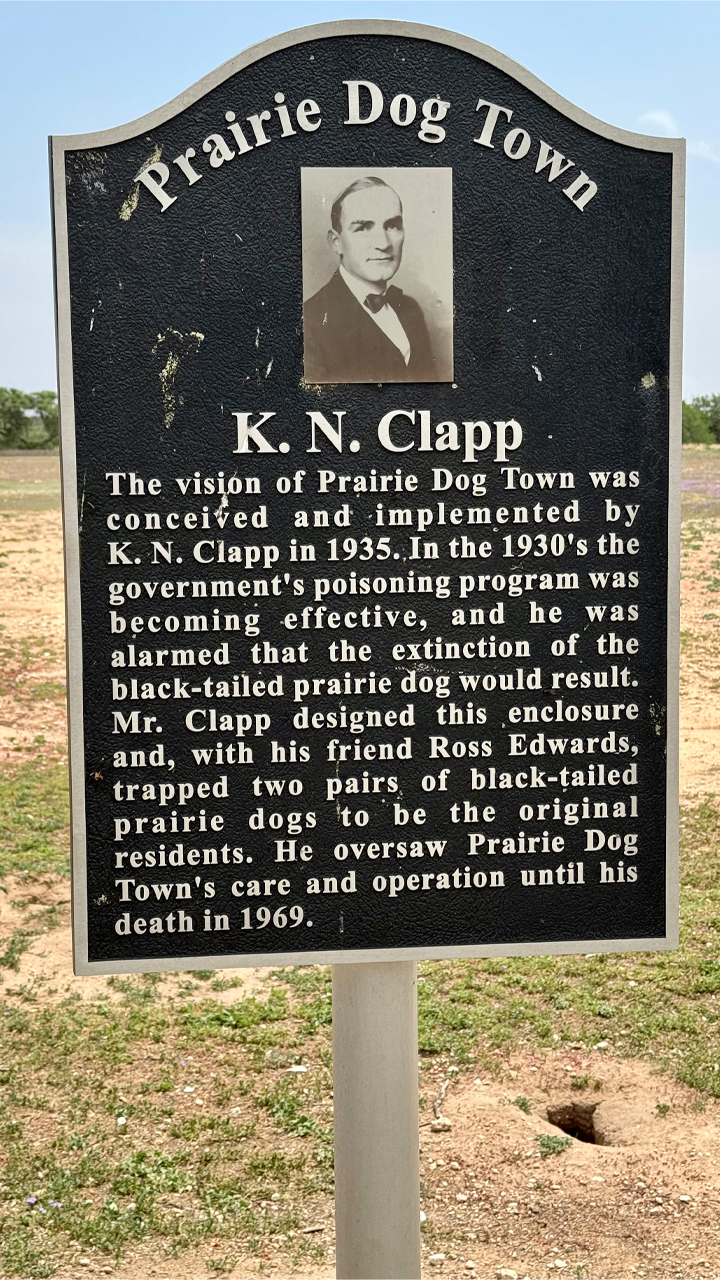

Kennedy N. Clapp was long-time chair of the city’s park board and a naturalist.

According to an historic marker at Prairie Dog Town, “In the 1930s, the government’s poisoning program was becoming effective, and he was alarmed that the extinction of the black-tailed prairie dog would result.”

Clapp and a friend trapped two pairs of prairie dogs. That was the start of Prairie Dog Town, which moved to its current location in 1935.

“Within its first five years at its new location, Prairie Dog Town became world famous and a favorite tourist attraction,” the website said.

Clapp was named the forever mayor of Prairie Dog Town.

Lubbock has a mascot, Prairie Dog Pete and a 2004 study showed Prairie Dog Town as the fifth most visited attraction by out-of-town visitors.

Witcher said, “I think it’s part of our culture. Red Raider Outfitter even had prairie dog merch that they were selling earlier this year.”

The Howdy Dog and Rootin’ Tootin’ lines of merchandise are still for sale.

When Whealton first came to Lubbock in 2017, “By going to the Prairie Dog Town, I wasn’t just seeing prairie dogs. I was also connecting with what has been a treasured experience here for generations,” she said.

Eradication and controversy

In April, the city began an eradication program in the Canyon Lakes System using carbon monoxide.

“Last year just along the Canyon Lakes, I think we estimated over 200,000 burrows,” Witcher said.

“They are impacting some of our neighborhood parks,” Witcher said.

“How many burrows were there in May of 2023 versus how many burrows were there in 2011 – it’s shocking,” she said.

It’s a safety issue for kids playing soccer, baseball or softball on a field full of holes, she said.

“We have to protect our city assets,” she said.

Nobles said the city has certain legal protections. The protection includes ‘sovereign immunity’ which we covered here.

“However, the more important issue is how to protect our citizens. … The city is absolutely concerned about kids and adults getting hurt on ball fields or parkland. This potential for injury is what primarily guides our efforts.” Nobles said.

City Manager Jarrett Atkison added, “I would note that regardless of legal liability, there is a general human liability and expectation that the city works to protect our citizens from obvious dangers.”

Kelly said the local Audubon Society objected.

“It seems unfortunate that the city feels they need to be eradicated. But yes, they do have to be managed,” Kelly said.

The Audubon Society tried to build a better relationship with city officials, she said.

“I’m not sure where we stand right now. They didn’t care for us voicing our concern about their eradication,” she added.

Nobles said in response to Kelly’s concern, “The department does consider these viewpoints when determining direction of care of the parks. The department must also consider all users of the park system and strives to provide safe and secure outdoor recreation that meets the needs of the citizens of Lubbock.”

The city is “spot treating” problem areas, Nobles said. There has not been a widespread effort for several years and there won’t be one again until later this year.

Keystone species

“The black-tailed prairie dogs are not a protected species per se,” Kelly said.

But the burrowing owl is. They and other species rely on burrows created by prairie dogs.

“The burrowing owl is already a species of international conservation concern. We are one of the top areas, really, in the world for breeding pairs of burrowing owls,” Kelly said.

Other creatures also depend on them. Kelly mentioned rabbits, snakes, lizards, hawks and coyotes. Seaberg added prairie chickens and the Black-Footed Ferret. Plants and bugs also depend on the burrows.

“A lot of good native grasses get cultivated by prairie dogs,” Seaberg said.

“Some farmers even want to utilize prairie dogs for cultivating better crops through crop rotation, and some even use them in ways to assist in fire-risk and suppression on their lands,” Seaberg added.

Prairie dogs reduce the amount of stuff that can burn on a grassland, according to the non-profit Watershed Center. Burrowing can benefit the soil by mixing soil types, according to the Great Plains Restoration Council.

“Prairie dogs do more than just serve as prey; they also perform a valuable service for the prairie – they disturb it. In addition to digging up the soil, prairie dogs clip the vegetation around their burrows, enhancing nitrogen uptake by these plants,” the council said.

“We spend so much time focusing on elephants and rhinos and precious resources in other countries, but we don’t take care of what’s in our own backyard,” Seaberg said.

Kelly said, “I personally can’t relate to the people who hate them. It’s just beyond my comprehension to not appreciate the natural world.”

Seaberg approaches it a little differently.

“If we can find ways to conserve them, I think that’s the smart way to go,” she said.

Rescue efforts in West Texas

Seaberg spoke highly of efforts by Lynda Watson to safely relocate prairie dogs to safe habitats including Caprock Canyons State Park.

“She’s done an amazing amount of work to help move prairie dogs to where they’re more wanted,” Seaberg said.

Nationally famous TV personality Mike Rowe did an episode of Somebody’s Gotta Do It with Watson.

“I’m gonna go ahead and admit it, he’s cute,” Rowe said on camera while holding a baby prairie dog.

Watson floods a burrow with soapy water. The prairie dogs come to the top and she grabs them.

Once in the new environment, she digs a hole for them and drops them in.

But that’s not all. She sprays them with perfume to discourage predators. She surrounds the new place with tinsel and American flags soaked in pine-scented cleaner. The smell discourages predators until the prairie dogs can dig a new town for themselves.

Also along the lines of preserving prairie dogs, please do not feed them Cheetos or Doritos or other junk food, Seaberg asked. Timothy hay, grass-based hay, fresh wheat and small quantities of fresh produce are all helpful, she said.

Natalino said, “I go out and me and my friends do this least a couple times a year. We go out and throw bales of hay.”

She also takes some romaine lettuce, watermelon, sweet potatoes, corn on the cob and carrots.

Natalino was featured by local news in 2018 for having 19 prairie dogs in her apartment.

“I got my first prairie dog actually when I lived in Connecticut back in 1993,” Natalino said. For a time, the federal government restricted prairie dogs as pets.

“When I moved to Texas, there was just such a need,” she said. Natalino described prairie dogs that could not go back into the wild, but they were also not suitable as pets.

If you ever think about getting one as a pet, Natalino said, “Do your research. They’re not easy animals. They’re cute, but they’re not easy.”

“They still have those wild instincts. They can bite,” she said.

Comment, react or share on our Facebook post.

Facebook

Facebook