(Cloe McCullough, image courtesy of Lori McCullough)

Cloe McCullough woke up in the emergency room.

“You are very fortunate. We’ve already had four other cases today … not as fortunate as you,” a nurse told Cloe about deadly fentanyl overdoses.

Cloe started crying, telling her mother Lori, “Mama, why me? Why did I survive, and they didn’t? Especially if we are all God’s children, why did I survive, and they didn’t?”

“Honey, I’m sorry. I don’t know,” Lori answered.

Lori McCullough cries while recalling that day in May almost two years ago.

Lori found Cloe and called for help. The response is captured on a body-cam video. One dose of Narcan usually brings a person back. It took five doses before they could get Cloe to the hospital.

Tony Williams, a Lubbock County Sheriff’s Department sergeant with the Texas Anti-Gang Center (TAG), uses that video in presentations to raise awareness about the deadly epidemic fentanyl has become in Lubbock.

Cloe did well in rehab for almost a year.

Then fentanyl got another chance to attack Cloe.

What’s fentanyl and how it’s abused

Fentanyl is a strong synthetic opioid to manage severe pain. It’s about 50 times more potent than heroin and 100 times stronger than morphine, according to the National Coalition Against Prescription Drug Use.

Drug dealers put fentanyl in counterfeit pills looking like legitimate prescriptions for Xanax or Adderall, routinely used by college students. Seven out of 10 bogus fentanyl pills have a lethal dose, said Williams during a presentation to the Rotary Club of Lubbock last month.

Dealers use young women to infiltrate Lubbock college parties. Many times those women are also sex trafficked, said Williams.

Some of the pills are made with bright, fun colors – like candy – so they’re more enticing to children. Williams talked about a 12-year-old Lubbock child who overdosed.

The seriousness may not be completely understood by the public because stats are not coordinated.

“We do not have a good system right now between medical and law enforcement to record this. Also, if they get a pill with multiple drugs in it, they will not call it a fentanyl overdose. They’ll call it an acute drug overdose,” Williams said.

There’s an effort to compile numbers on this problem locally, said the Lubbock Police Department. Some people go directly to a hospital without police intervention. The city’s Health Department is working on it. The district attorney and Medical Examiner’s office are also working on some way to get numbers, Williams said.

And there are new drugs coming – at least one that Narcan cannot help.

Williams also shared tips on what parents can look for that could save their child’s life.

Start talking to kids at age three

Parents sometimes talk to their kids in high school or even middle school about the dangers of drugs. Williams suggests starting at age three if they can understand the words because of how bad the situation has become.

He showed pictures of fentanyl disguised as common medications – some of which are legal with a prescription – at the Rotary presentation. The pictures mostly came from Lubbock-area drug busts.

“They almost look like Flintstone vitamins,” Williams said of one photo.

Williams made a similar presentation to the Lubbock City Council in early January.

“This is made for children. Those pills do not look dangerous. We call them rainbow pills. And we were buying these consistently here in Lubbock,” Williams said.

Cartels also use images of cartoon characters to promote the pills, Williams said.

“They see Woody handing out rainbow pills,” he said of some packaging.

“The youngest overdose that I’m aware of in Lubbock is a 12-year-old Cavazos junior.” Williams said.

He tries to get into schools to talk to kids between 6th and 12th grades.

“But if I had a three-year-old and they could understand me, I would start talking to him now.”

Williams presents anywhere people will listen, especially schools. He estimates he’s got in front of 10,000 kids locally and looking to do even more.

Clean until she wasn’t

Cloe was salutatorian of her Smyer High School graduating class.

“She did all the things – band, basketball, tennis,” Lori said, including going to tennis regionals her senior year.

“Very successful,” Lori said, adding her daughter didn’t do drugs.

Cloe got a full scholarship to South Plains College toward her goal to be a surgical tech.

That’s when she started struggling with addiction.

She was wary of drugs, Williams said.

“But she thought pills maybe weren’t that dangerous and that’s all it took,” he said.

“We knew Cloe had started vaping,” Lori said. “We were not happy, but, I mean, she was over 18. And then … she had started drinking too.”

Cloe wrote her mom a letter during this time.

“I’m not gonna let it happen to me because I know the signs. I’m not gonna let it happen to me,” Lori said Cloe wrote.

There was another person in the family who struggled with addiction, Lori further explained.

‘Very good’ counterfeits

One pill can kill, Williams says over and over. One pill can also cause an instant addiction.

“No one ever says it feels bad,” Williams told LubbockLights.com in a follow up conversation. “The most common term they use is, ‘It takes their soul,’ which is kind of scary. Then they said they just melt into a seat. They said it feels amazing.”

But the withdrawals are vicious, he said.

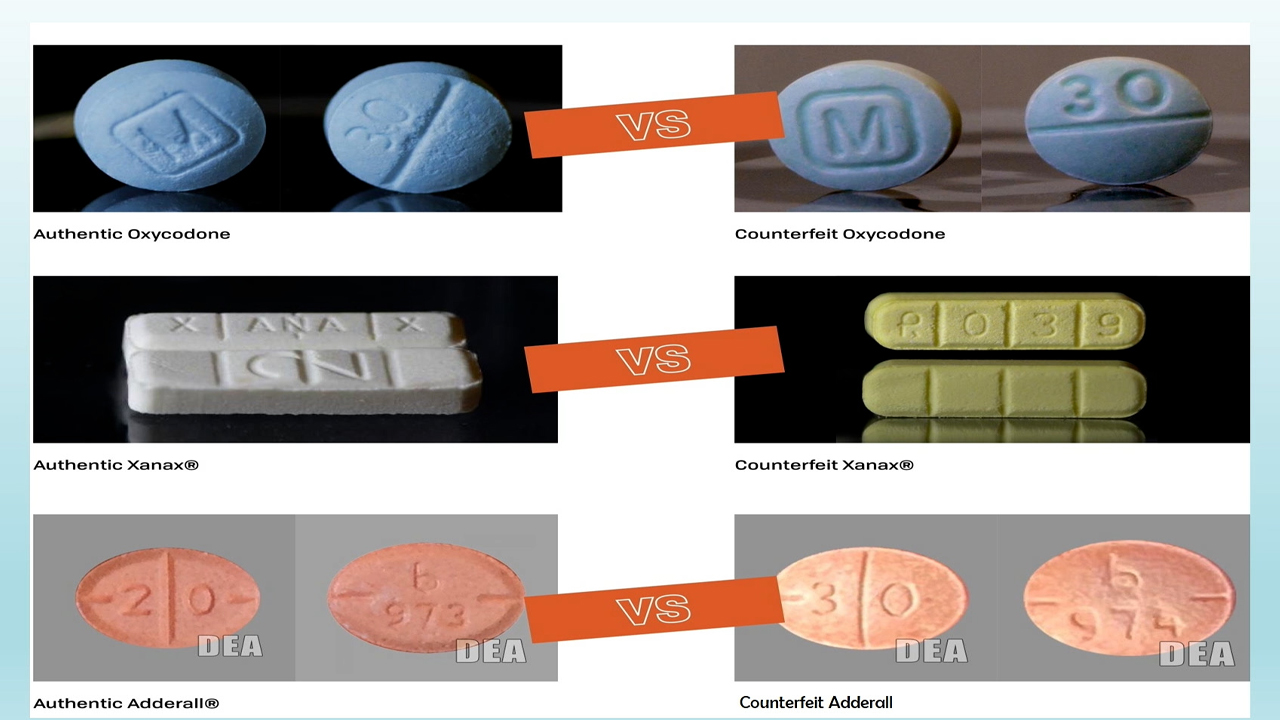

In his Rotary presentation, Williams showed pictures of legitimate prescription pills side-by-side with counterfeits.

“The cartels are making very good counterfeit pills. The colors are spot on. There’s no way to tell,” he said.

As one example, Williams showed a pill stamped with the ID “M30.”

A press release from federal prosecutors in a 2022 case explained, “Fake prescription pills known as ‘M30s’ imitate Oxycodone obtained from a pharmacy.”

Williams also showed a pill marked as R039 – disguised as Xanax. Adderall too.

College students sometimes want Adderall to stay awake after a night of partying. But you can’t judge a pill by its shape, color or ID stamp.

An officer cannot just confiscate prescription medications for no reason.

“I can’t say, ‘Let me send those to the lab and I’ll get your medicine back,’” Williams said.

Cloe’s overdose on video

Williams showed the body-cam video from the day Cloe overdosed. A deputy ran into the family home into Cloe’s bedroom. A second deputy is preparing Narcan.

“This deputy saves her life – 100 percent,” Williams said.

“Usually, Narcan will wake somebody up with one dose. They hit her with five doses, and it kept her alive long enough to get to the hospital,” he said.

Cloe got into treatment, attending AA meetings and therapy. She moved to a sober living home in Dallas.

“They recommended her not coming back to Lubbock because of the people here – her friends,” Lori said.

“We talked every single day. She knew Tony had been using her video,” Lori said, adding it was shown at Smyer ISD where Lori teaches and all three of her daughters went to school.

“She was starting to get up during her AA meetings and starting to share things,” Lori said. Cloe learned a new motto. Be afraid and do it anyway.

When Cloe learned Williams was using her overdose video in presentations, she told her mom, “I really want to help,” Lori said.

“That might really help them make it more personal to them – more real to them – how dangerous this is,” Lori said.

There were plans, but Cloe never got to present the video with Williams.

7 out of 10 are deadly

LubbockLights.com asked Williams why the cartels would make most of their pills with a lethal dose.

“Their tolerance grows rapidly,” Williams said. So, a regular user wants the higher dose.

“Seven out of 10, for me, would be a lethal dose,” Williams said. “But an addict that’s using 40 pills a day, well, that’s probably not going to be the same.”

It’s a two-edged sword.

“They build a tolerance really quick, but it also falls really fast,” Williams said.

Being in jail or rehab for a while is enough to lose tolerance.

“Their tolerance is really low,” Williams said. “They think they can use the same amount, and then we’re seeing the overdose.”

At the same time, the people making these drugs see death and suffering all the time, Williams said. They don’t care about overdose deaths.

Burnt straws, balled-up foil and emojis

Williams gave a list of things parents should notice:

• Burnt straws in their backpacks.

• Multiple pens taken apart.

• Balled-up foil.

Tin foil with burn marks? Users figured out the pills are sometimes not the right dose and taking a pill is too risky.

The solution is to put a pill on the foil and use a lighter to heat it. The users have a straw or a hollowed-out pen to sniff the vapor.

Emojis can advertise drugs. The Drug Enforcement Administration provides a list of common emoji codes used on social media:

• A snowflake emoji can be used to promote a cocaine dealer.

• A blue heart or a diamond can indicate meth.

• A yellow and red pill can indicate Xanax or Adderall.

Lori had no idea about the emojis until she saw Cloe’s phone.

“She gave us her phone … ‘Here’s this,’” she said.

“This” included a symbol next to someone’s name to indicate a drug dealer.

“I didn’t look at her phone until I had a reason,” Lori said, adding she believes it’s OK for parents to check their children’s phones.

Sex traffic and rat poop

The biggest fentanyl dealers in Lubbock in 2022 had young women helping. Williams wanted to know why.

Once caught, the young women were going to snitch. The only other choice is a long prison sentence, Williams said.

Dealers – after arrest – told Williams why they used the women.

“I can’t walk into a Texas Tech party or an LCU party and sell pills. But that girl right there can,” Williams said.

“These girls were so addicted to drugs that they also get sex trafficked. This is how sex trafficking starts,” Williams said.

He pointed to a mug shot lineup in his Rotary presentation.

“This young lady was a cheerleader at a school here,” Williams said. “She said, ‘Once I tried those pills, it took my soul.’ There’s no way these young ladies would be sex trafficked by these guys without this drug.”

Williams questioned a suspect in Lubbock who was making pills. The young man showed Williams a garage that was “so nasty.”

“You could taste what it smelled like.” Williams said. “I don’t know if you’ve ever been in a place like that, but he was pretty sure that was McDonald’s French fries and rat poop in the pills that he mixed.”

Very few pills are actually made in Lubbock anymore. It’s just cheaper to drive to El Paso or Arizona, Williams said. A dealer can pick up hundreds or thousands of pills for 80 cents each and sell them for $21.

Cloe’s life, and relapse

Chloe was one of three daughters.

“They’re all less than two years apart. The three of them were extremely close. She was the baby of the three,” Lori said. “It’s no fun. They’ve lost a sister.”

Cloe loved reading books, including Harry Potter, climbing trees, putting puzzles together and juggling.

“She could juggle while riding a hoverboard. She was very talented. She was so kind and non-judgmental,” said her mom.

At one point Cloe took a mission trip to Africa.

“That really touched her life,” Lori said.

During treatment for addiction, Cloe wrote to her mom.

“I have renewed my relationship with God, and I feel like I have a purpose again in life,” Lori said of Cloe’s letter.

“She just had a moment of relapse, which is part of recovery,” Lori added.

Williams said, “She used it one more time and it took her life.”

The Russian

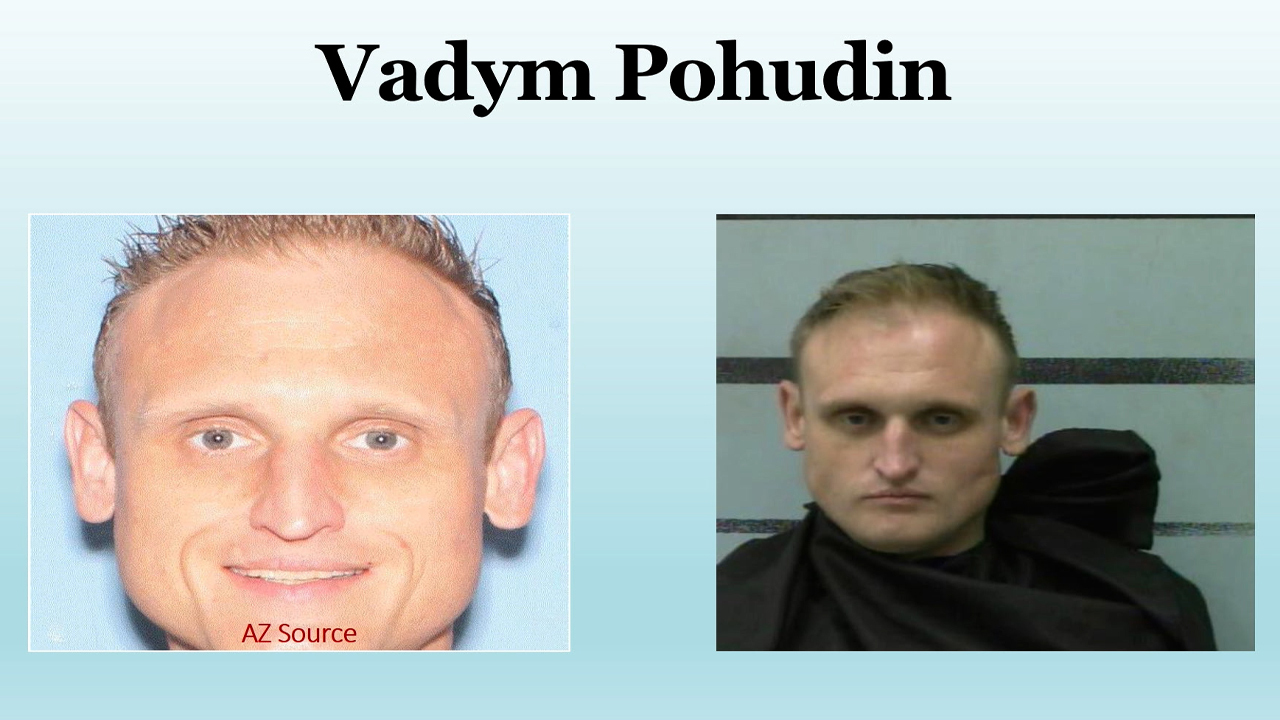

Williams presented images of Vadym Pohudin, saying, “He was a criminal in Russia. He got to Mexico.”

“He walked to the port of entry, like they say to do. He had fake visas, so they couldn’t identify him,” he said.

“They gave him his papers. He got a court date in about 90 days. Obviously, he didn’t come back. He ended up in Lubbock,” Williams said.

Pohudin got caught dealing drugs and was arrested.

“I asked him, ‘Why Lubbock?’ He said, ‘Well, y’all got Texas Tech University. You have South Plains – you have LCU, Wayland Baptist University,” Williams said.

Pohudin set up shop in a hotel in Northwest Lubbock, Williams said.

“He said there’s tons of college kids right there in walking distance,” Williams said.

Pohudin was able to drop the price from roughly $30 per pill to a range of $5 – $7. He believed there was a “hit on him” meaning someone was trying to kill him for dropping the price so much, Williams said.

“He said that ‘I saw these people taking these pills. So, I decided to try them. That’s all it took. I was instantly hooked,’” Williams said of his interrogation of Pohudin.

About a year ago, Pohudin was sentenced to 13 years in prison.

Faith going forward

Lori keeps leaning on her faith.

“In my life, it is the only way I’m surviving right now. We serve a mighty God who is so faithful to show His love in so many ways. And I need to document it all,” she said.

Lori feels God is telling her, “Yes, your baby’s with me right now, but I love you still and I’m taking care of her, and she’s okay.”

More trouble looming

“We haven’t seen fentanyl on the vapes yet, but we did just seize a large amount of liquid fentanyl. So, it’s a matter of time before we do see that,” Williams said.

There’s more.

“Carfentanil is used to tranquilize elephants,” Williams told the City Council while showing a picture. The same stuff in tranquilizer darts can be put into a pill.

“One that we’re starting to see, which is really kind of scary, is called Xylazine,” Williams said. Xylazine users get skin ulcers. But one thing makes Xylazine worse.

“The only drug that can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose is Narcan,” Williams said.

“If that pill, which we are starting to see, has Xylazine in it, Narcan will not work.”

Comment, react or share on our Facebook page.

Coming soon, we will offer a weekly newsletter to highlight our work. Use the form below so you don’t miss a thing.

Facebook

Facebook