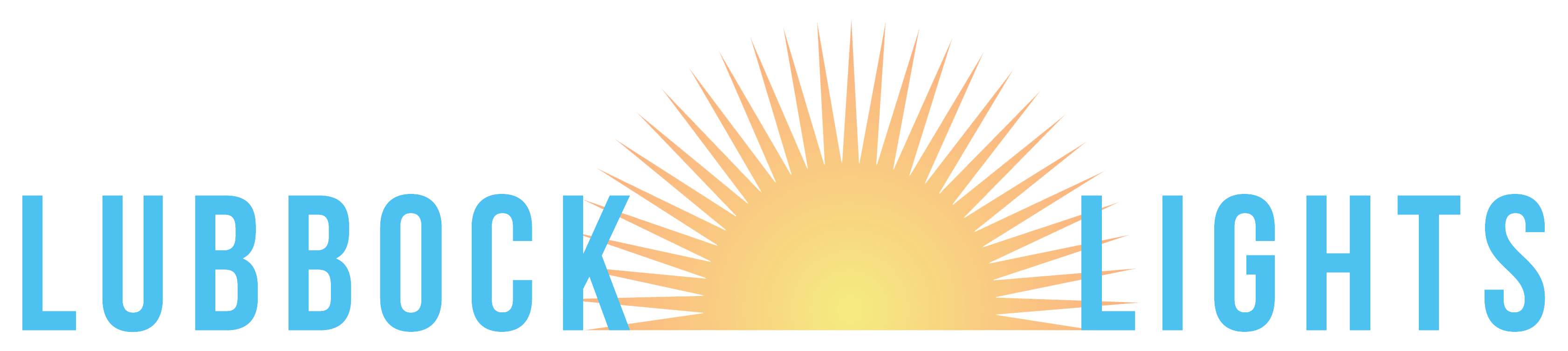

Rose Wilson, image by Olivia Raymond

In Lubbock in 1955:

- Elvis Presley played the Cotton Club.

- Monterey High School opened its doors.

- Rose Wilson moved to town.

There was immediate impact from the first two events. The third, however, took a few years for people to recognize, including Rose herself. But after a landmark court case changed Lubbock in 1983, the city learned her name.

“Miss Rose” (as friends call her) made an impact.

The 96-year-old has served on boards, mentored young people and pioneered change.

Granddaughter Tonya Johnson calls Rose “a little spitfire.”

She wasn’t yet a spitfire when born in Bryan, Texas in 1927. Her family had a cotton farm and raised cows. She and her four siblings helped on the farm, Rose especially, as she was the oldest. By the time she was in elementary school, her family moved to Houston. Rose graduated high school at the same time WWII was ending.

She married quickly after graduating – leaving frustrating arithmetic behind – focusing on bigger issues.

She married Otis Knowles, who she’d met in school and they started a family.

1950s

In the following years, Rose had five children, got divorced and was looking for a change of scenery by the middle of the decade.

Rose had a friend trying to get away from an abusive marriage and was moving to Detroit. Rose thought about joining her friend in Motown.

“I visited Detroit and was up there for a while, but I began to think, ‘No, I’m goin’ back to Texas,’” she said.

Rose’s mother and sisters had moved to West Texas where they found work on a cotton farm in Lorenzo. Lubbock was not where she envisioned living.

The rural setting was a stark contrast to city life, but Rose being near family was a good idea.

In 1955, Rose and her five kids moved to Lubbock.

Slideshow: images of Rose Wilson by Olivia Raymond

1960s

“Lubbock was a very different place back then,” Rose recalled.

Lubbock was still segregated, like most of the American South.

The Black population was not allowed to live west of Avenue A, relegated to the east and northeast parts of town.

Rose took a job at the downtown Luby’s Cafeteria. As cashier, she met all kinds of people. One customer took interest in Rose, who can’t remember the woman’s name but says she can still see her face. The woman lived in a large house near 32nd Street and Avenue Q. Her husband was a rancher.

As she got to know Rose and learned she was raising five children, the woman decided to help.

The downtown Sears was only open to Anglos at the time. But Rose’s new friend took Rose and her children with her into the store, insisting each child pick out a school wardrobe.

More than 60 years later, Rose still remembers.

“You don’t forget when someone does something for your kids,” Rose said.

Rose eventually transitioned to cleaning houses. She started with a few clients, getting more business by word-of-mouth.

Rose’s family became part of the East Lubbock community. Her kids were active in their school, Rose serving as a volunteer at Iles Elementary. They regularly attended church. And after a few years in Lubbock, Rose even adopted a sixth child, one of her cousin’s kids.

“I had three boys and two girls; I decided I should even it out,” she said.

Rose continued to build her house-cleaning business. As her reputation grew, so did her client base. She soon knew many of the “other kind of people” in town.

“That’s what I call the Anglos and I learned quick if you wanted to get anything done, you needed the help of the other kind of people,” she said.

1970s

Rose was raising children and making a living.

Meanwhile, Gene Gaines, Lubbock’s first Black lawyer, was making waves. His wife died and he wanted to bury her up front in the Lubbock Cemetery. He was told his wife had to be buried in the Black/Mexican American section. Angered, he decided to sue the city.

“That’s how it all started,” Rose recalled, with an index finger to her temple.

Gaines’ first lawsuit was unsuccessful. Eventually, he started looking at the larger picture. Decisions such as segregation in burials and other civil rulings were largely decided on at the City Council and mayoral level. There were no minorities on the council, let alone mayor.

The city charter of 1917 excluded any Black or Mexican-American citizens from holding positions of leadership.

Because all people elected to the council served “at-large” – meaning they didn’t represent a specific district as they do now – only white people were getting elected.

African Americans didn’t even account for 10 percent of Lubbock’s population at the time. Statistically speaking, it was almost impossible for a minority candidate to win a council seat.

“Gaines’ next lawsuit was about getting single-member districts across the city council,” Rose said.

While the lawsuit had supporters, Gaines took his case to court without plaintiffs and was “tossed out on his butt,” Rose said.

“That judge told Gaines, ‘If you’re going to represent Black people you better have some Black people when you come back,’” Rose recalled.

While Gaines didn’t have much success getting the lawsuit off the ground, many Lubbock citizens instantly saw merit in the idea. Gaines also was not experienced in civil rights litigation. Dan Benson, a professor at Texas Tech University’s School of Law, heard about the lawsuit and volunteered to be lead counsel.

Benson, with a group of young volunteer lawyers working pro bono, filed the suit again.

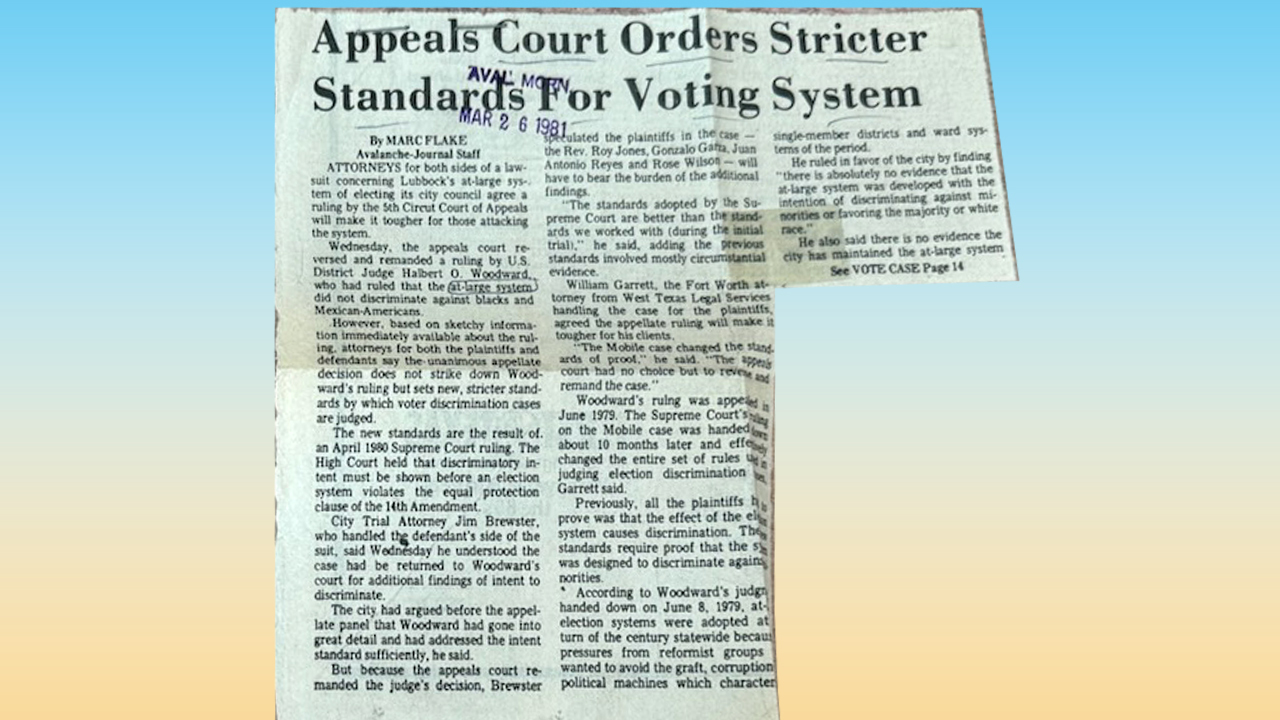

This time, they did so with four plaintiffs: the Rev. Roy Jones, Gonzalo Garza, Eusbio Morales and Rose Wilson.

Over the next seven years, the case would go to court two more times.

Rose was reluctant to get involved at first.

“The League of Women Voters was supporting the lawsuit, as was the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP),” Rose recalled.

At the time, she wasn’t involved in either.

“I was a housekeeper keeping up with a bunch of kids,” she said.

The League of Women Voters first approached Rose’s mother about becoming a plaintiff, she suggested they talk to her daughter. One of the women in the league happened to be a woman who employed Rose.

“One day I went to clean her house and she told me, ‘Rose, I’d like for you to come with me to a meeting,’” she recalled. “I didn’t know a thing about the league or the case at that time.”

When she arrived, the women filled her in on the lawsuit.

“They asked me if I would consider being a plaintiff,” she said.

Rose answered honestly; she didn’t know, wanting to know more about the case and what would be involved. She didn’t have the luxury of taking time off work, even for something important with six children to raise.

After oscillating back and forth for some time, Rose decided she couldn’t do it. It was going to be a long, messy legal battle and she wasn’t sure if it was her fight.

“I was cleaning a house one day when three of the women from the league came over. They told me, ‘We want you to stay on; we got you a lawyer from Washington D.C.,’” she said.

Rose was a central part of the lawsuit from that point on. The plaintiffs were Black or Mexican American – the demographics being underrepresented. Each had their own lawyer representing them, provided by either the League of Women Voters or the NAACP.

The first time Benson brought the case before a judge, they lost.

In a historical article for the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal, attorney Chuck Lanehart wrote, “Sentiments ran hot on both sides of the controversy. Mark C. Hall (one of the volunteer lawyers) remembered, ‘At trial, we had to open up a lot of old wounds that had been healing over time.’”

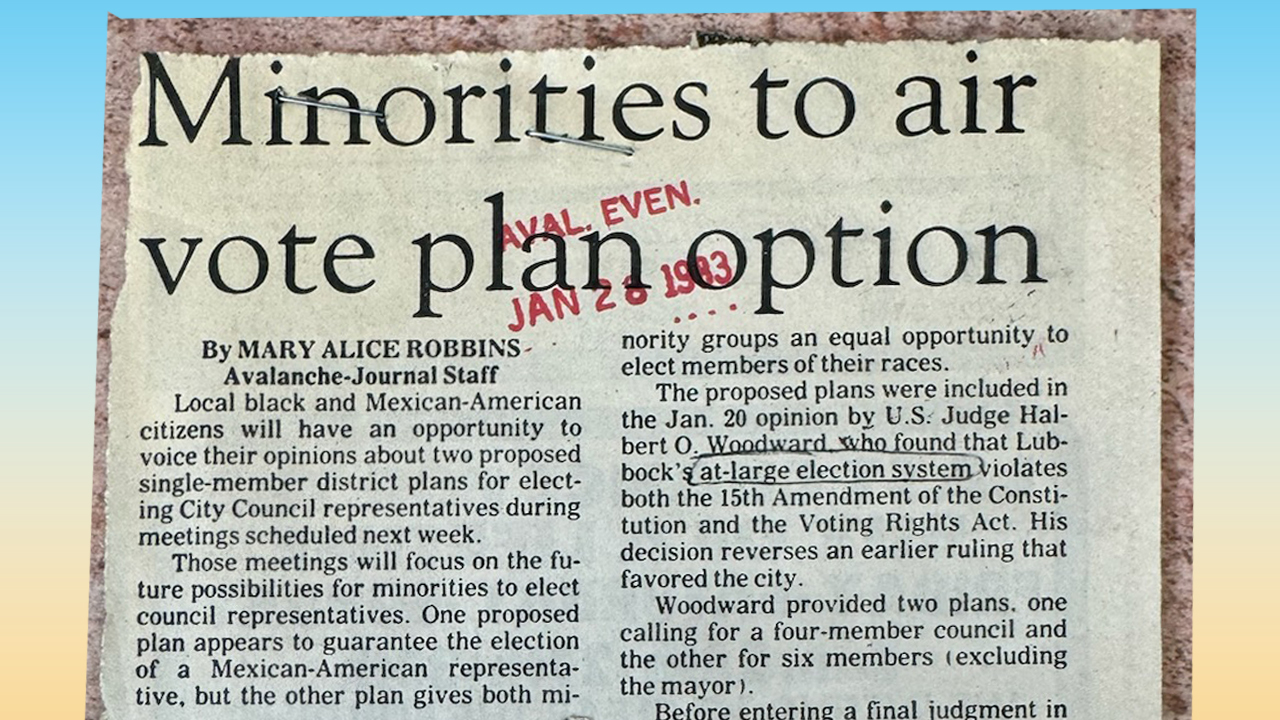

After the initial loss in 1979 in judge Halbert O. Woodward’s court, Benson and plaintiffs appealed to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans.

Meanwhile, legislation was changing nationally. The U.S. Supreme Court made decisions that would support the plaintiff’s argument.

1980s

In the early 1980s, the case was remanded back to Woodward’s court.

One of the leading plaintiffs, Rev. Roy Jones, stepped away from the case.

“That’s how I became one of the big dogs in it,” Rose laughed, shrugging.

Community members rallied around Rose, helping subsidize her income, watch her children and deliver meals while she was in court.

When the case was retried, it leaned on the evidence provided in 1979. The principles of the case had not changed, but the law had. Woodward determined the city’s at-large system based off a decades-old city charter, violated the 15th Amendment and Section Two of the Voting Rights Act.

“The room was packed that day. We’d been up there for weeks; we were exhausted but I had a feeling we were going to win this time,” Rose said.

Rose doesn’t quite recall the words that came out of the judge’s mouth next but remembers the shouting.

“It was a hallelujah day for us,” she said with a smile.

Not letting go

The details of the new city council had barely been written out before Rose’s peers suggested she run. She considered it a bit, but ultimately decided against it.

“I thought, ‘No way,’” she laughed.

Her life had been upended for the better part of seven years. She was ready to return to normal. However, when she tried, Rose realized there was no more “normal.”

She’d boarded a fast-moving train that was hard to get off. She also didn’t want to. She’d been part of something bigger than herself, catching hold of something intangible yet essential.

Rose wasn’t letting go.

“The fight for equality became personal to me after that trial. I started seeing things that’d keep me up at night,” she said.

She’d change what she could. What she couldn’t change, she’d pray about.

“What we achieved now had to be maintained and there weren’t people lining up to do that,” she said.

Around this time, a minister in town approached her about running for president of the local chapter of the NAACP.

“I told him, ‘Are you crazy? They don’t want no woman,’” Rose said.

It turned out they did. Rose agreed and while she was skeptical about her ability to win, she kept getting more support.

During the elections, a fellow contestant asked, “You all want a maid for a president?”

“That really bothered me at the time,” Rose recalled.

It bothered her so much she considered dropping out of the race. Rose was talking to her mother one day and told her she might give it up.

“Did God tell you to give it up?” her mother asked.

“No,” Rose replied.

“If you walk away from this Rosie, you’re going to let people down. Not just African Americans, but this whole community.”

Rose won election as the chapter’s first female president, holding the office more than 30 years.

Membership boomed under Rose. People of all colors and backgrounds joined, resulting in the chapter Lubbock knows today.

Rose’s legacy

The U.S. recently celebrated Juneteenth – known as “Jubilee” or “Emancipation” Day – celebrating the official end of slavery.

On June 19, 1865, federal troops arrived in Galveston to ensure the proclamation was carried out. Texas was the last state to put the emancipation proclamation into effect, finally signaling the end of the Civil War.

Rose’s great-great-grandmother never lived to see that day. Her great grandmother was alive when the decree made its way to Texas. By the time Rose came along, five generations had passed but some attitudes hadn’t changed.

A hundred years later, progress had been made, but segregation and other racist laws and attitudes stalled further progress.

Rose has seen much of it.

Rose’s mother came to Lubbock picking cotton. Years later, her daughter was honored with the Governor’s Lifetime Volunteer Achievement Award in 2022. Rose is the amalgamation of many hopes and prayers from over the years. She knows this and it’s why she has invested so much into the next generation.

Beyond serving with the NAACP, Rose has volunteered her time to:

- Lubbock Habitat for Humanity

- Texas Access to Justice Organization

- Legal Aid of North Texas

- Many other organizations.

She’s built friendships with politicians on both sides of the aisle. She calls Republican State Senator Charles Perry a friend and recently appeared on Texas Democrat Beto O’Rourke’s TikTok account.

“Rose is an energetic person who wants to make things equal for everyone,” said Milton Lee, current president of Lubbock’s NAACP chapter. “She has a charisma that everyone is drawn to. Lubbock has seen a lot of change over the years and Rose has been a part of those

changes.”

But more important to Rose are the relationships she’s built with young people. She’s invested in hundreds of young people in east Lubbock, starting with her family. Granddaughter Tonya Johnson moved into her grandmother’s house when she was 9 years old.

“The thing I remember most is whenever something significant was happening in the public eye, my grandmother had us in front of the television,” Tonya recalled.

Rose made sure her family was informed and educated, wanting them to understand how the world impacted their community and she wanted to hear their thoughts about it. It rubbed off – Tonya was on the Lubbock Juneteenth Celebration Committee for a decade.

“I remember thinking from a young age, ‘I want to be like Miss Rose when I grow up,’” Tonya said.

Lubbock would be a different city without her grandmother, she said. Voting would work differently, there’d be less awareness of the NAACP and a lot of kids might have gone down a different path.

Slideshow: images of Rose Wilson by Olivia Raymond

“My grandmother believes things can change, and that makes others believe it too,” Tonya said.

Rose knows her legacy will live on in the actions of those who love her. She also knows with every victory comes new opportunity. She sees the future similarly to how she saw it in 1983.

She told the Southwest Digest newspaper after the conclusive victory in court, “It was a long, hard fight, but I’m glad it’s over and I’m glad we won. All we have to do now is wait and see where we go from here.”

Comment, react or share on our Facebook post.