Traveling exhibit in Lubbock, Military Mapping Maidens

A traveling exhibit featuring female World War II heroes is in Lubbock until the end of August because an Arizona woman learned to say “yes ma’am” to a 98-year-old Ohio woman.

In 2019, long before Michelle Reid brought “Military Mapping Maidens” to Lubbock’s Silent Wings Museum, she was working on a museum project in Arizona when a man said, “You need to meet my mom.”

Mom was Bea Shaheen McPherson – one of 224 women who drew maps to help win WWII. Only two of the women are still alive.

Reid – a museum professional and World War II historian – recalled meeting McPherson.

“She came out to Arizona for the holidays, vetted me over the course of lunch, and asked to see my work. So, we toured another exhibit.”

“I guess I was okay. She informed me that I would be making an exhibit about her life and the life of the other women who drew maps. And when a 98-year-old woman says that to you, the only answer you have is, ‘Yes, ma’am,’” Reid said.

They started down a path ending with the exhibit showing how the “maidens” used the then-new technology of aerial photographs and how the maps were made and used.

Also, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt contributed to a bit of a map shortage in the country that made their mission even more critical.

Where: Silent Wings Museum, 6202 North Interstate 27

When: Until August 31, 2024

Admission: $10 general admission (click here for exceptions)

Spirit of ’45 Day: August 10, 2024 – free admission (observed on Saturday, not Sunday in Lubbock)

Description: The story of 224 young women in the Army Map Service who researched and drew maps by hand for the Allied war effort.

Exhibit name wasn’t a victim of cancel culture

Reid consistently referred to McPherson as Bea.

“She called me often. … If she couldn’t get ahold of me, she called my husband, at which point he would give me the phone and say, ‘Your boss is on the line.’”

McPherson was no respecter of time zones. Ohio is either two hours ahead of Arizona or three depending on whether Daylight Saving Time is in effect. Reid described a phone call at 3:30 a.m.

“And I had to pick up the phone,” Reid said.

“And there were a few tense moments, a few times when I got it wrong. … At one point, the conversation went something like this. ‘Michelle, this is Bea. I don’t think you know what you’re doing.’ To which I said, ‘Yes ma’am.’”

McPherson turned 102 in December and, “She is still going strong,” Reid said.

Reid told her Lubbock audience another problem she had in developing the exhibit was the “darn name.”

“Military Mapping Maidens. Bea calls them the 3M girls – just as bad,” Reid said.

It was a different time. For example, women in the American Red Cross were called Doughnut Dollies.

Reid’s response was to rhetorically and exasperatedly ask, “Really?”

“You’ve got a number of these that maybe are not acceptable today. And so, when it came to titling the exhibit, I toyed with a lot of different things, and Bea kept calling and saying, ‘No. We were the Military Mapping Maidens. It was cute,’” Reid said.

“Yes, ma’am,” Reid told McPherson.

Long hours hunched over a table

The worked in secret in a Washington D.C. building covered by camouflage netting, Reid said.

“The gravity of their work was immediately apparent,” Reid said.

They used guidebooks and tour books, tourist documents, and gazetteers (geographic reference books).

The government asked people to send in these materials – an early version of crowdsourcing, Reid said.

And they the newfangled idea of aerial photographs.

“They weren’t supposed to know where they were drawing. Their work was very compartmentalized. Some drew land features. Some drew man-made features, but they knew something was going on. It wasn’t until after D-Day that they learned that that’s what they had been producing,” Reid said.

But along the way, every once in a while, the maidens figured out which map they were drawing.

“They were working on a set of maps and one or two of the other map makers had traveled to Italy and they were able to identify what they were drawing as Fiume in Italy.”

The work was hard – 12-hour shifts – about 70 hours a week.

“[Bea] talks about four female colleagues hunched over a drafting board and ‘hunched,’ is exactly the word that she uses,” Reid said.

Queen Bea

“She describes her work in such detail. It’s crazy. She closes her eyes, and she draws in the air, and she mimics what she was doing – while she’s telling you, of course, what she was wearing,” Reid said.

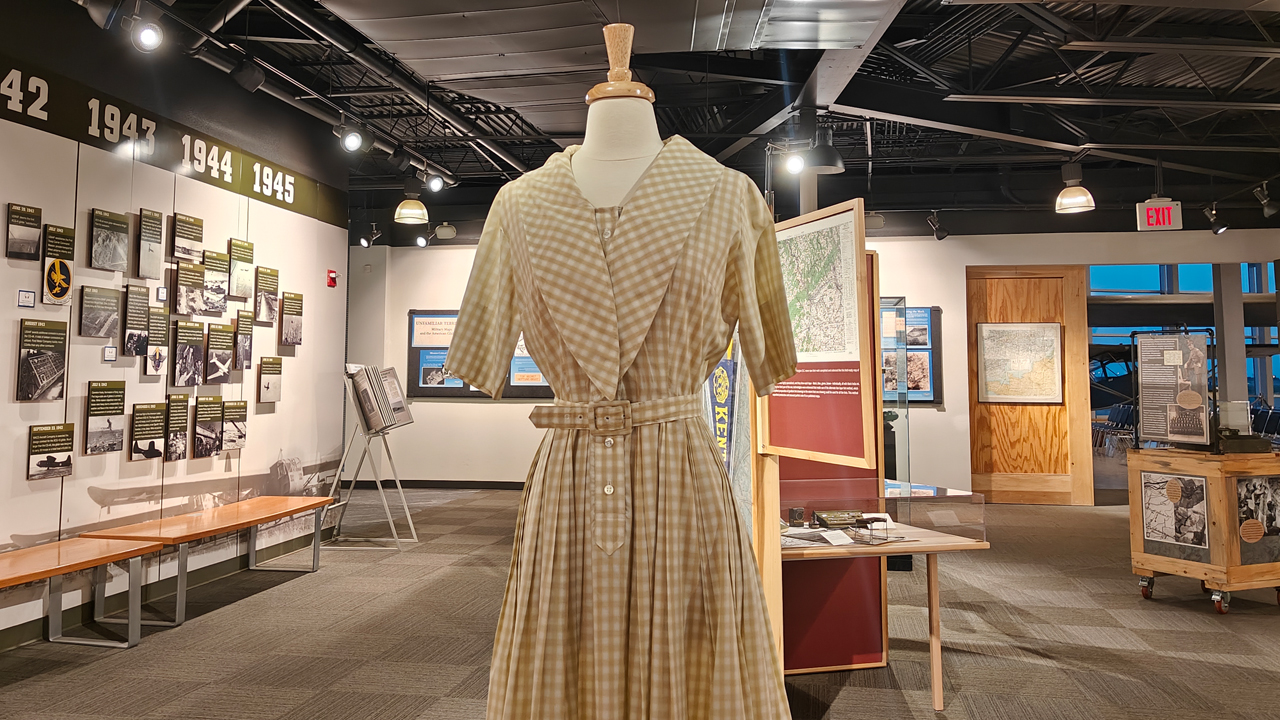

The exhibit includes a ball glove, softball, game dress and saddle shoes.

“That was so important,” Reid said of the clothing and fashion.

McPherson turned 100 years old when Reid debuted the exhibit for the first time in Canton, Ohio.

“I think there was a crowd of 250 people. She was the lady of the day. And she liked it a lot. It was a fantastic event.” Reid said.

Much more quiet

Reid also interviewed the other remaining map maiden, Dina Morelli Kennedy, who lives on the East Coast.

“Kennedy was much more quiet about her service. She was uncomfortable with, I think, the notoriety. But … she had great stories to tell,” Reid said.

“She was a researcher and chosen for that position because she was fluent in French and German. So, she went through books and she found pictures of cathedrals and pictures of bridges and then was able to correlate those two locations, identify them on aerial photos and then instruct the map makers where to draw them,” Reid said.

A dearth of maps

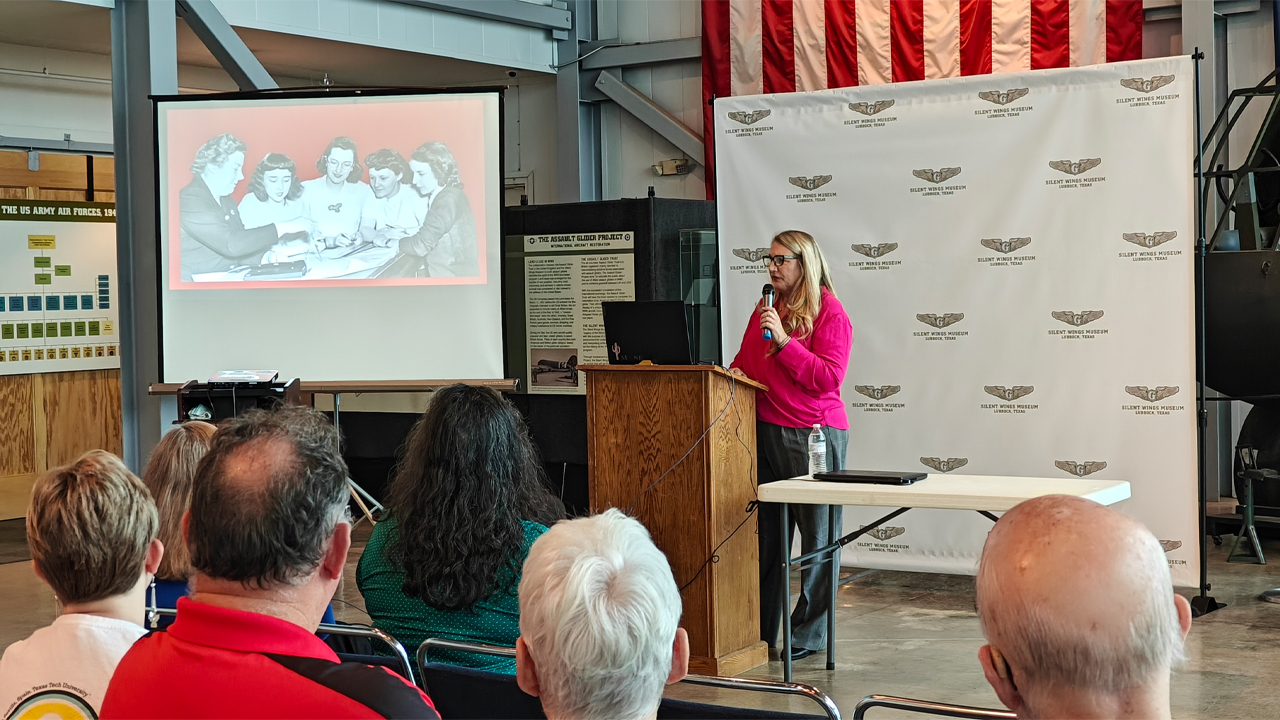

Reid introduced Lubbock to her exhibit Friday evening at the Silent Wings Museum to a crowd of roughly 30.

President Franklin Roosevelt, in his Fireside Chats broadcast nationwide on radio, encouraged Americans to purchase world maps, she said.

“He says, ‘Get your maps out. I will walk you through what’s happening around the world.’” Suddenly, every map is just disappearing,” Reid said.

That wasn’t the only reason America needed more maps. The map shortage was even more intense for the armed forces.

The Library of Congress website said in 1941, the 77th Congress passed a bill to fund maps of areas around the globe the Secretary of War deemed strategic.

“The federal government found their existing map coverage to be inadequate for the war … ” the library website said.

As men were drawn off to serve in military roles, the army recruited young women to study cartography at select colleges or universities. From there, the army provided additional training.

McPherson and her fellow maidens made nearly 14,000 new maps that were copied and shipped nearly 400 million times.

The connection to Lubbock

In WW II, pilots came to Lubbock to earn their ‘G’ wings at the South Plains Army Air Field – now called Lubbock Preston Smith International Airport. Technically, the ‘G’ stood for glider, but the pilots had a different story.

“Every one of them would say that isn’t a ‘glider G.’ It’s a ‘guts G,’ because we’ve got to have guts,” said Sharon McCullar, Silent Wings Museum curator.

There was glider training in other places, but those paths led to Lubbock.

Nearly 80 percent of the nation’s combat glider pilots trained in Lubbock. They flew the CG-4A glider sometimes called a flying coffin but more affectionally known as “silent wings.”

The American Society of Mechanical Engineers website said, “Combat gliders represented the state-of-the-art in stealth, landing precision, and hauling capacity.”

No engine meant no noise. The Americans could sneak past the German or Italian lines especially at night. Gliders were also used to repel Japanese forces in China.

The training was extensive, as was the use of gliders, Reid said. More than 12,000 CG-4As were made, according to the National Museum of the United States Air Force.

It’s hard to say exactly what McPherson’s impact was on the gutsy gliders.

“Based on my research and what I’ve learned from this fantastic museum, the most likely connection we have with our map makers and glider pilots is through Operation Overlord,” Reid said.

Operation Overlord was the codename for the D-Day allied invasion of Normandy France.

Comment, react or share on our Facebook post.

Facebook

Facebook