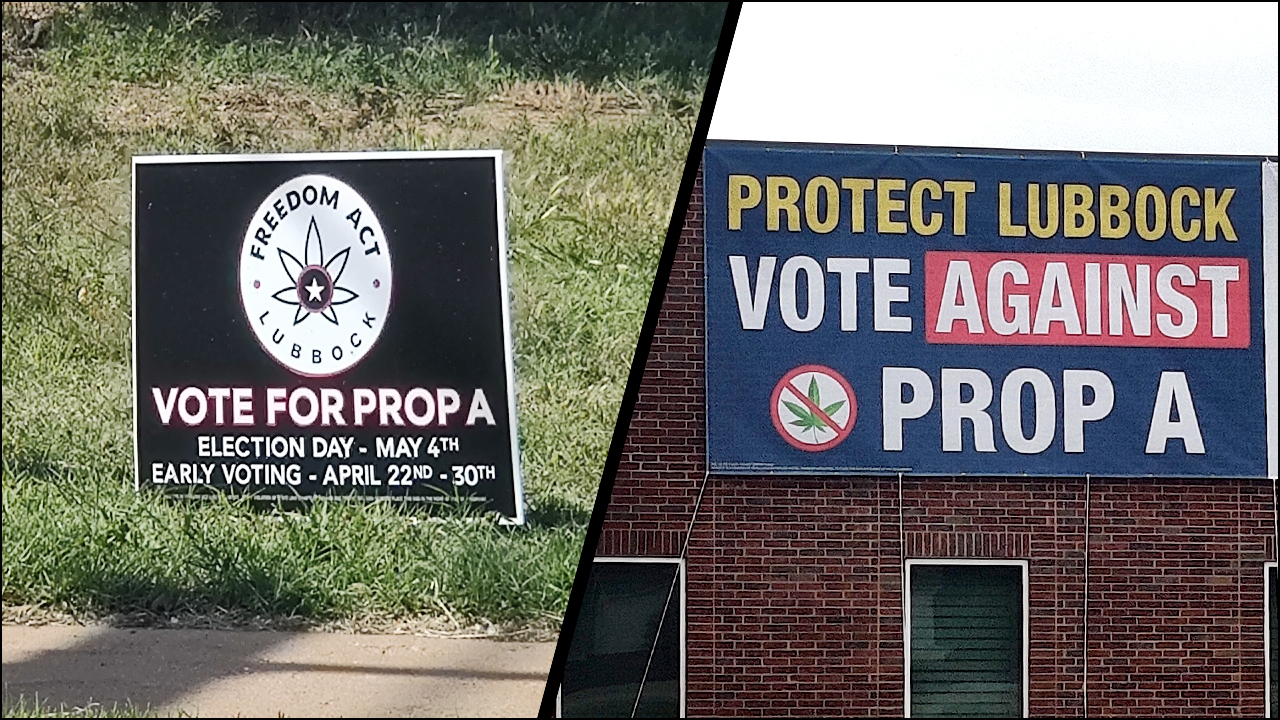

Signs in favor and against Prop A, composite image

Joshua Shankles and Kelly Rowe disagree on the marijuana initiative on the city of Lubbock’s May 4 ballot.

Rowe – Lubbock County Sheriff – was told in early March about six drive-by shootings, “all involving marijuana,” he said.

“Thinking that marijuana is harmless and all that – I’m sure you probably have a pretty specific viewpoint on that. But that being said, six drive-by shootings in six days,” Rowe said.

Shankles, a founding member with Freedom Act Lubbock, has a different story.

While gathering support for the marijuana initiative, a veteran “covered in decorations” approached him.

“The guy’s limbs were very seized up. He was very stiff all over,” Shankles said. “He was like ‘Oh yeah. You know this saved my life. This is the only thing that reduces my pain. This is the thing that makes me feel good. This is the thing that allows me to continue my life.’”

While the ballot initiative is not about medical marijuana, for Shankles, that’s not the point. He wants Lubbock to “rebalance” its enforcement of marijuana by decriminalizing it.

The sheriff disagrees and adds if the measure passes, it only directs the Lubbock Police Department, not his deputies.

Local voters will settle the debate May 4 with early voting beginning this coming Monday (April 22).

There could also be impact beyond Lubbock and we’ll explore that in this story.

Recapping the proposal

The proposed ordinance goes to voters as Proposition A.

If passed, it says in part, “… The Lubbock Police Department shall not make any arrest or issue any citation for Class A or Class B misdemeanor marijuana possession.”

State law limits a misdemeanor possession to four ounces or less.

The Lubbock City Council rejected the proposal in November with several council members wondering if such an ordinance is legal under state law. Sunshine Stanek, Lubbock County criminal district attorney, asked Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton for a legal opinion. So far, the AG hasn’t responded and the opinion may hinge on lawsuits Paxton filed against other cities for their marijuana ordinances.

A relatively new state law says local governments “may not adopt a policy under which the entity will not fully enforce laws relating to drugs.”

The proposed ordinance has a special legal technicality built in. If one part of the ordinance is found to violate state law or a court order, then the rest of the ordinance remains on the books.

Lubbock’s ordinance, if it survives the ballot box and legal challenges, calls for decriminalization, not legalization.

What’s at stake

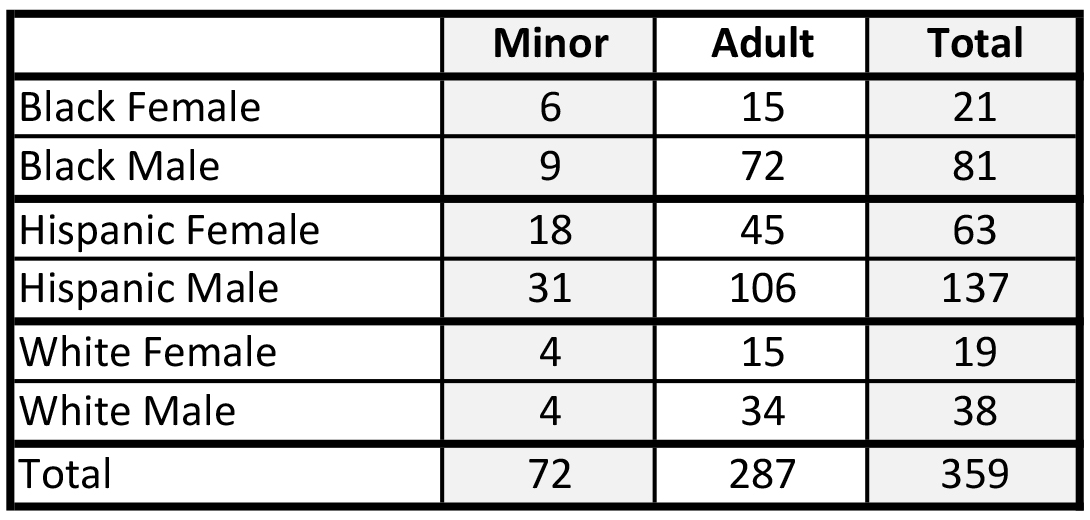

Proponents say marijuana arrests hit minorities disproportionately. Opponents say an arrest for low-level marijuana by itself is not all that common. Here are the numbers.

The Lubbock Police Department said in the last three years (from March 1, 2021, through March 1, 2024), the department arrested 359 people for misdemeanor marijuana possession “with no additional charges.” That’s under one arrest every three days.

Hispanics are 56 percent of those arrested for misdemeanor marijuana with no other charges. African Americans are 28 percent, and Whites are 16 percent.

According to the Census Bureau, Lubbock is nearly 38 percent Hispanic, 8 percent African American, 51 percent White (not Hispanic) and two percent Asian. Roughly two percent are two or more races.

The maximum penalty for a Class A misdemeanor is up to one year in jail or a fine up to $4,000 or some combination of the two. The maximum penalty for a Class B misdemeanor is up to 180 days in jail, a fine up to $2,000 or some combination.

Rowe said his jail is over capacity – with some local inmates going to other jails to make room. But they are generally for pre-trial felonies (more than 70 percent) – not a standalone marijuana charge, he said.

“I have one – and I mean one – inmate sitting in there on … a convicted misdemeanor,” Rowe said to LubbockLights.com.

“We’ve got much bigger priorities and much bigger call volumes than worrying about whether college kids got a couple of joints,” Rowe said.

And Texas Tech’s police department, he said, is “judicious” about making an arrest for marijuana.

“I mean, it’s just not happening,” Rowe said.

Amy Ivey, a captain with the Texas Tech Police Department, said, “Officers enforce all state and local laws. They use officer discretion when it comes to misdemeanor marijuana violations.”

An officer can release someone while a charge is pending with the District Attorney’s Office, or an officer can arrest someone on site.

State Representative Dustin Burrows (R) of Lubbock said officers can already decide not to arrest someone for marijuana.

“They’re making good decisions about when to prosecute and when not to,” Burrows said.

Drive-by shootings

Rowe speaks publicly against the marijuana initiative, saying it’s not a victimless crime, citing the drive-by shootings. The problem is not people failing to pay their dope dealers, he said.

“The biggest part of it is competition. People are competing for curb space. They’ll put a social media post up and say, ‘Well, I’ll be sitting in the parking lot of … some location. If you want some weed, I’ve got it for you,’” he said.

Sometimes someone will pose as a dope dealer just to rob a prospective buyer at gunpoint, he said.

Rowe is not convinced decriminalization makes the situation better – citing Colorado as an example where marijuana is legal.

“Do you think for a second that stopped the illegal trade from happening?” he asked, adding illegal cartels can sell it cheaper than legal dispensaries.

Kevin Caldwell, the southeast legislative manager for the Washington-based Marijuana Policy Project, said states can lower taxes on legal marijuana to curb illicit sales.

The Vicente Law Firm with offices in Austin and Denver studied legal marketplaces in 24 states, he said.

“Every year that the legal marketplace grows and grows, more people – with time – leave the illicit marketplace,” Caldwell said.

Caldwell’s organization does not think marijuana should be unregulated. For example, driving while high is a bad idea. But he thinks legal is better than illegal.

“Texas has a multibillion dollar a year cannabis industry currently, but it’s untaxed. It’s unregulated,” Caldwell said.

For better or worse

Places that legalized marijuana do not have a better quality of life, Rowe said, pointing to Portland.

USA Today in March said Oregon was the first state to decriminalize illicit drugs and the first to reinstate criminal penalties for use and possession. The change did not include marijuana and comes amid an increasing problem with fentanyl.

Rowe also pointed to Seattle, where he said homelessness there was recently described as “bleak” and a “crisis.” A columnist for the Seattle Times pointed to poverty and a lack of affordable housing. Marijuana was not mentioned in the column, but drug abuse was. For Rowe, there are just too many before-and-after stories of places where marijuana was made legal.

Caldwell saw it differently, saying, “Of the 24 states that have legalized the adult use of cannabis, there has not been one serious attempt to roll that policy back.”

Let the punishment fit

Shankles was among those who gathered signatures to force a public vote.

“The motivation behind Freedom Act is that we are using the criminal justice system to deal with people who have, in many, many cases committed a victimless crime,” he said.

He described the “magnitude” of consequences that do not stop with an arrest. People lose jobs and gain a criminal record. Sometimes others are relying on that person as the family breadwinner.

“To the degree this is a problem for anybody, it’s a problem best solved in a healthcare setting, not a criminal justice setting.”

In many cases the opponents raise good points, and he sympathizes with the criticism that Proposition A is best handled at the State Capitol, Shankles said. But he said the state has been unresponsive to a majority of Texans who favor fewer restrictions on marijuana.

“The rubber actually hits the road in our community,” he said.

Caldwell said, “We’ve seen polling that says that roughly 75 to 80 percent of Texans support decriminalization.”

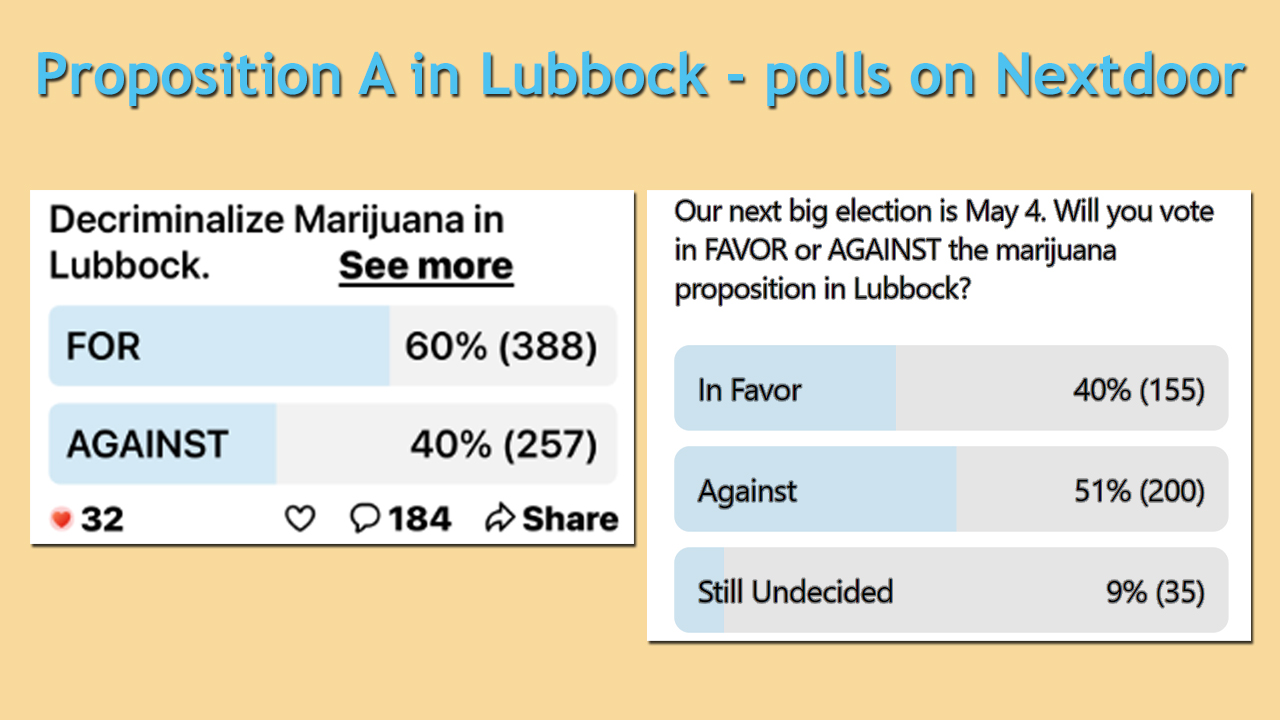

The polling

Here’s what some official and unprofessional polling shows.

A Texas Tribune/University of Texas poll said, as of December, 17 percent of Texans believed marijuana should not be legal for any purpose. That’s down from 27 percent in 2010.

The poll found 30 percent agree small amounts should be legal for any purpose. That number has ranged from 26 to 32 percent over the years.

It found 34 percent believe small amounts for medical purposes should be legal. That number ranged from 26 to 34 percent since 2010.

A poll in Lubbock on the Nextdoor app started on February 17 and gathered 645 total votes as of Monday. It showed 60 percent “for” and 40 percent “against.”

A separate Lubbock poll on Nextdoor, started on March 12, gathered 390 votes with 40 percent “in favor,” 51 percent “against” and 9 percent “still undecided.”

More agendas

Burrows thinks this vote is not about marijuana.

“You are seeing groups of community organizers trying to identify voters and get them out in these municipal elections to vote for issues. It’s not only statewide, but nationwide,” he said.

“If they are successful with one of these, they move on to the next and next and more progressive left-leaning issues to try to change the culture of the cities and perhaps the state and country,” Burrows added.

“They start with decriminalization of marijuana, and then they start pushing for defunding the police,” Burrows said.

Rowe expressed a similar concern – the movement builds a rolodex of voters who are willing to push progressive issues.

Shankles rejected that idea.

“The organizers of this particular measure have less than zero interest in efforts to ‘defund the police,’” Shankles said,

Regardless, Burrows said if it passes in Lubbock and withstands any legal challenges, then he’s glad to introduce more legislation.

“This is a state issue, not a local issue,” Burrows said.

“However, if there is a loophole, certainly I would be wanting to close it, because it’s a horrible idea to have a patchwork of laws about drugs. You shouldn’t have to drive through Idalou to Wolfforth through Lubbock and wonder where’s marijuana legal or illegal,” he said.

Efforts to legalize marijuana at the state level will likely continue. Burrows wouldn’t venture a guess on whether that’s inevitable in Texas.

“However, I do not expect that Texas will legalize recreational marijuana use in the next legislative Session,” Burrows said.

Confusion

Police officers would be impacted by the ordinance but not sheriff’s deputies or Department of Public Safety troopers, Rowe said.

“That’s one of my biggest concerns. It’s so much confusion. You’re going to have somebody thinking, ‘Hey, this passes I can have up to four ounces in my possession,’” Rowe said.

That won’t work if a deputy shows up.

“A full-size Ziplock bag, full to the brim, is four ounces. Four ounces is far more marijuana than a single user needs. That starts turning into a more deliverable amount,” he said.

The proposed ordinance does not mention ounces. It only refers to state law which sets the cutoff point for misdemeanors and felonies.

Questions for the other side

LubbockLights.com asked Shankles, Rowe, Burrows and Caldwell to give three questions for those who disagree with their position.

Shankles asked:

- How would they suggest that we create a balance between public safety and compassion?

- How it is that the Sheriff’s Office is able to make a determination like 6 in 10 joints in Lubbock are supplied by drug cartels out of Colorado when they can’t interdict all the marijuana?

- How do they distinguish between anecdotes and what data tells them are the facts around this issue?

Rowe answered:

In balancing justice with compassion, Rowe said, “That again is part of the argument that we’ve got all these folks losing their jobs; you know, it’s breaking up families.”

Rowe doesn’t think that’s happening. But if it is, he thinks the State Capitol is the right place to change the statute.

As for whether a batch of weed comes from Colorado or Mexico, Rowe said often you can smell it. He says Mexican Skunk Weed has its name for a reason. He said stuff grown in the states is likely to be hydroponic, and there’s “probably” involvement from cartels.

In distinguishing facts from anecdotes, Rowe said he can pull up cases or statistics on the department’s computer system.

“We can pull up cases from a straight data perspective,” Rowe said.

Rowe asked:

- I would expect that you’ve seen where decriminalization or legalization has been done in other cities and seeing what that has done to other cities. How will this be any different?

- Why is there is no distinction between different types of marijuana – in particular, hydroponic marijuana and its levels of THC versus the products we see coming in from the south of Mexico. How can you not recognize the difference?

- So, if this were to pass, what’s next? Using San Marcos as an example, their very next step was to try to defund police.

Shankles answered:

The sheriff asked about negative impacts in other cities and how would Lubbock be any different.

“Long story short, we don’t know how it will be any different or similar to any other city. … No one does,” he said.

He went on to say the ordinance was crafted to limit the disproportionate impact on minority, low-income, and young adult communities.

As for no distinction for hydroponic marijuana, Shankles answered, “As a former farmer and someone rather familiar with hydroponic and other growing practices, there is nothing particularly outstanding about hydroponics.”

Soil-grown vegetation can also provide high or low density of nutrients to the plants, he said.

The sheriff wonders what comes next.

“‘What’s next’ is, we rest!” Shankles said. And that’s the same, he said, if it passes or fails.

Burrows asked:

- If this is truly a local issue, why have so many other ordinances popped up across the state and country with similar language and similar goals?

- Are they going to promise that once they pass this, they’ll never consider passing another ordinance? Or are there other things in mind?

- Who is funding the lawsuit against the state preemption bill that I passed? (This is a reference to the so-called ‘Death Star’ bill in Texas.)

Caldwell (and Shankles) answered:

Burrows wanted to know, if this is a local issue, then why is there similar language and similar goals all over?

“Cannabis prohibition is an incredibly popular issue among voters, people want to see this,” Caldwell said.

Instead of reinventing the wheel, people copy and paste the ordinances where it already passed, he said.

As to Burrows’ concern of more progressive initiatives coming up, Shankles said no.

When asked about funding the legal challenges to Burrows’ legislation for uniform regulation of business in Texas (the so-called Death Star bill – HB 2127), Caldwell said he didn’t know but he was glad someone disagreed with Burrows.

“What’s the point of a city having a home rule charter if they’re only allowed to pass legislation that the state likes?” Caldwell asked.

While HB 2127 is not about marijuana, it does seek to keep business regulation the same from city to city in Texas. Burrows thinks it needs to be same for marijuana as well.

Caldwell asked:

- In an era of police resources being scarce and overstretched, do they believe that continuing cannabis prohibition is the best use of those police resources?

- With a criminal penalty associated with a possession arrest – not being able to get an education, not be able to get housing, or losing a professional license – do they feel that those consequences fit the nature of this crime?

- Whereas we see in legal states, ID checks are much better within the cannabis industry than it is say for alcohol. What would they recommend for keeping people under 21 from having access – the same way a regulated marketplace would?

Burrows answered:

Caldwell asked about enforcement while police resources are scarce.

“I don’t accept the premise of his questions. I think the fact local law enforcement is against this proposition speaks to the fact that he bases his questions on a false premise,” Burrows answered.

Caldwell asked if the penalties are too harsh for simple possession. Even before seeing the question, Burrows said he trusts officers to make good decisions about when to prosecute.

“The officer already has that discretion to not take that young person to jail,” Burrows said.

Burrows did not answer Caldwell’s question about ID verification and keeping those under 21 from getting marijuana. The proposed ordinance in Lubbock also does not address that question.

Coming soon, we will offer a weekly newsletter to highlight our work. Use the form below so you don’t miss a thing.

Comment, react or share on our Facebook page.

Facebook

Facebook