(Photo above: Dick Standefer receives the Bronze Star. All photos courtesy of Mike Standefer, except Canham painting.)

Head coach Dell Morgan wanted to motivate his 1946 Red Raider football team.

He was yelling.

Someone came up to Morgan – who led Tech for ten seasons – reminding the coach some of his players recently returned from Europe, where they dodged death, killed Nazis and saw friends die.

A different approach was suggested. Morgan adjusted.

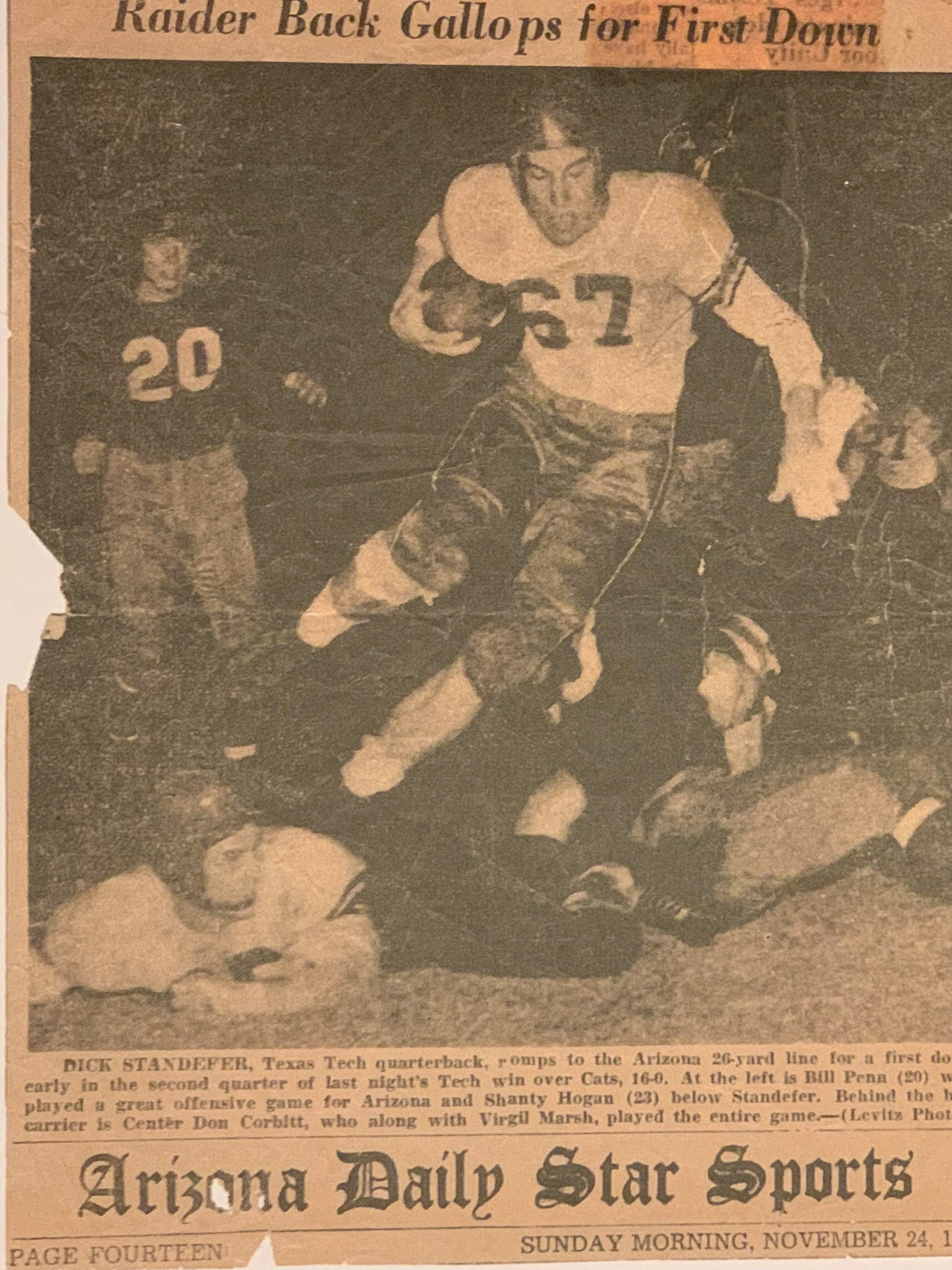

Tech had an 8-3 season highlighted by the school’s first win over Texas A&M. Tech’s quarterback for most of that season was Dick Standefer, who’d impressed Tech coaches when he played high school ball in nearby Muleshoe.

Standefer lettered at Tech in 1942 and ’46.

In between, he landed with the 8th Infantry on a French beach four weeks after D-Day, marched across France and into Germany, helping America and its allies defeat the Nazis.

Dick Standefer was the epitome of West Texas tough, said his son Mike. Like his dad, Mike lettered as a Tech football player, wearing the same number 67, before becoming a Naval aviator and Delta Airlines pilot.

Dick died in 1984. He was and remains Mike’s hero.

A strong arm built from throwing hay bales

Eugene Richard Standefer was born in August of 1923 – the same year Texas Tech was born – in a dugout near the Briscoe County town of Silverton, about 70 miles northeast from where he’d star for the Red Raiders.

His grandfather bought 180 acres in 1900 near land owned by Charlie Goodnight, legendary trailblazer, Indian scout and rancher.

“They were kind of the quintessential West Texas ranching/farm family,” Mike said of his ancestors.

The family moved to a number of South Plains towns before Muleshoe, where Dick was star quarterback, also playing defensive back when athletes played both offense and defense.

Throwing hay bales and baseballs made from tape-wrapped rocks gave him a strong arm. Milking cows produced a strong grip.

“Everybody said Lincoln Riley was the best quarterback to come out of Muleshoe, but my dad may have that claim,” Mike said.

Morgan and assistant football coach Berl Huffman came to Standefer’s games in Muleshoe, inviting him to play at Tech.

Collier Parris, a Lubbock Avalanche-Journal sportswriter, referred to Standefer in a column without naming him.

“There was the case of a Southwest Conference coach asking Dell Morgan of Texas Tech: ‘Now that kid over at Muleshoe, says he’s going to Texas Tech. Well, you’ve got so many ball players at Texas Tech you don’t know what to do with ‘em. And I need him! How’s about giving him his release so he can come to my school?’

“To which Morgan replied: ‘No, I don’t need him. I don’t need him anymore than I do my right arm, or any other hot prospect. Just let me catch you foolin’ around him and it’ll be me or you when the next session of district court meets,’” Parris wrote.

Parris is best known for coining the nickname Red Raiders, which legendary Tech coach Pete Cawthon adopted in the 1930s, replacing Matadors.

Dick played on the freshman Picadors team in 1941, before joining the varsity in 1942. The Red Raiders were 4-5-1 that year but finished 3-0-1 in Border Conference play, sharing the league title with Hardin-Simmons. Those teams battled to a 0-0 tie in the Nov. 21 game in Lubbock that season.

Before the 1943 season, 20-year-old Dick was off to war.

Winning a war while losing friends

Dick’s military training took him to Missouri, Tennessee and New Jersey before going by ship to Northern Ireland in December 1943.

A few months later, he went ashore at Utah Beach at Quineville, France, on D-Day Plus 28. It was the Fourth of July.

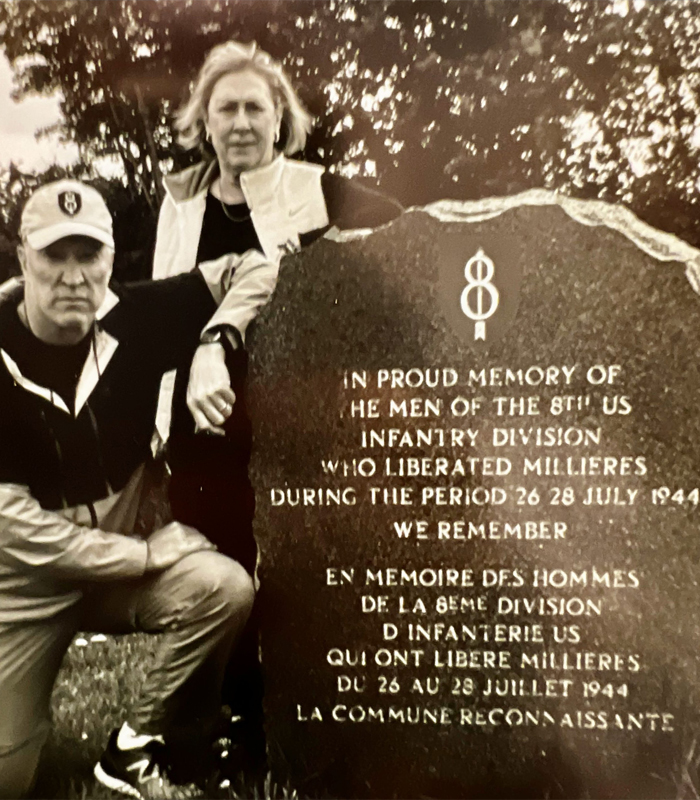

Mike, his sister Valarie and their spouses retraced Dick’s path across Europe a few years ago.

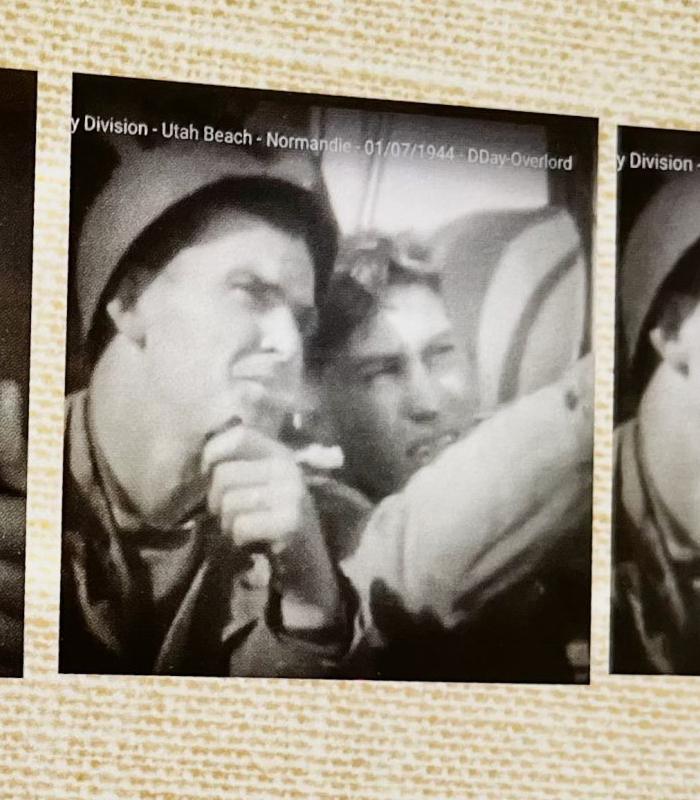

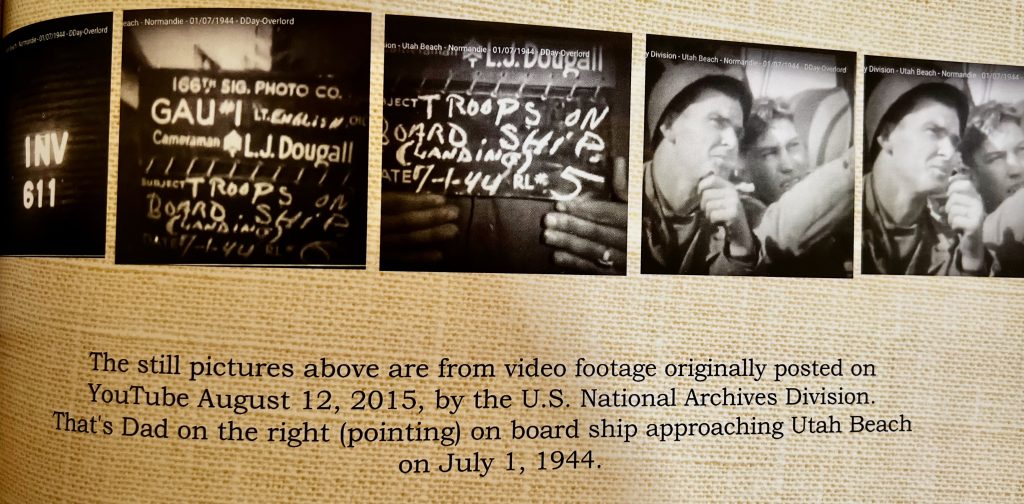

Inspired by that trip, Mike’s wife Cathy was searching the Internet and found a World War II newsreel of soldiers watching unloading of trucks and artillery to smaller vessels headed for Utah Beach. The newsreel focused on two men for about ten seconds. The man on the right looked like her husband. His teeth had West Texas water stains.

It was Dick Standefer.

Mike and his siblings were amazed – and a little saddened – when they saw the video. They saw a young man a month shy of his 21st birthday, unaware of the violence and horrors of war ahead of him.

After landing at Utah Beach, the 8th headed further inland, facing light skirmishes and casualties. The first hard combat came at the Ay River battling Nazis across the 20-foot-wide waterway. The Germans were driven back after 18 hours of fighting.

The Americans entered the village of Millieres after crossing the Ay River.

Today, a marker stands near the village, thanking for 8th Infantry for defeating the Germans, who were aided by a deadly Nazi sniper.

After the war, Dick was reticent to talk about his experiences. But one night, friends goaded him into telling a war story.

They heard about the war on the Cherbourg Peninsula.

Dick and his closest friend got separated during one battle. When the fighting stopped, Dick searched for his buddy, finding him dead, his face obliterated.

After Dick told the story, the friends never asked for another war story, Mike said.

After capturing the Cherbourg Peninsula, the 8th went more than 200 miles west to retake the port city of Brest.

They entered Brest quickly, surprised the Germans and demanded surrender.

The German commander asked to see his captor’s credentials.

Brig. General Charles D.W. Canham, pointed to his soldiers and their M1 rifles, telling the German, “These are my credentials.”

It’s the 8th Infantry’s motto to this day.

They turned east, across France, into Belgium and Luxembourg. Paris was liberated August 25th, Brussels Sept. 3rd and Luxembourg a week later.

The 8th was ordered to replace the 28th Infantry in the bloody Battle of Hurtgen Forest – on the Belgian-German border – which took place from September 1944 to February 1945, the longest single battle in American military history.

More than 100,000 U.S. troops fought in the battle, with an estimated 24,000 killed, wounded or captured, according to a 2019 article on warfarehistorynetwork.com (subscription required). Combat fatigue, pneumonia and trench foot claimed another 9,000 men.

Dick survived his time in the Hurtgen Forest during brutally cold weather, fighting in rugged terrain against a stubborn enemy trying to keep the Allies driving into their country.

The Germans won the defensive battle, then went on offense in the nearby Battle of the Bulge in Belgium. It was the bloodiest battle of the war for the Americans, but they won and the Third Reich was nearing the end of its brutal history.

The 8th did not fight in the Battle of the Bulge.

As the Americans drove into Germany in 1945, the 8th had to cross the Ruhr River. A pontoon bridge was built, floated into position and attached to the far shore so communication cables could be laid. After the bridge was floated, it took about four hours to secure it and push the Germans back far enough so troops could cross.

Dick was one of the first men across and received the Bronze Star.

The 8th helped liberate a couple of concentration camps and ended the war in Schwerin, Germany – between Hamburg and Berlin.

Meeting his future in a Plainview shoe store

Dick returned to West Texas on leave in 1945 and went to see his girlfriend in Floydada. They planned to marry after the war, Mike said. Dick discovered she’d married a man and already had a child.

That same year, Dick met Billie Jean Donowho, daughter of a Meadow blacksmith.

She’d moved to Plainview, where Dick’s family now lived, a bookkeeper at a shoe store where Dick’s father worked.

Dick was visiting his father in the store the first time Billie Jean saw him. Dick started to stand up and he “just kept standing up and up and up,” she said later. They didn’t meet that day. A few days later she was walking to work. Dick saw her, offered her a ride and asked her out to a movie.

Even though victory in Europe was in May of 1945, Dick wasn’t officially released from the Army until later that year, so he missed the 1945 football season.

That 1946 season and spurning the L.A. Rams

Dick was quarterback for the Red Raiders again in the 1946 season – playing games just south of where Jones Stadium was to open a year later .

Tech opened with a home win against West Texas State. The next game was against Texas A&M in San Antonio.

Tech entered as a heavy underdog, but the game was scoreless in the final minutes. Dick handed off to Charley Reynolds, a reserve halfback and Border Conference sprint champ. Reynolds sprinted around right end for a touchdown from ten yards out.

Reynolds had set up the winning score by intercepting an Aggie pass at the A&M 30 and returning it to the 13.

The Aggies got deep into Tech territory in the final seconds of the game, but the Red Raiders kept them out of the end zone to seal the school’s first win over A&M, 6-0.

Dick navigated Tech to that 8-3 record and was noticed – drafted by the NFL’s Los Angeles Rams. He signed a contract to be paid $5,000 for his rookie season.

The Rams told him they’d provide all his equipment but recommended he bring his own shoes because he might get blisters if he used the team-issued shoes.

Dick never reported to Rams camp.

His son Mike has a copy of a telegram the team sent Dick asking if he was coming to camp the day after he was supposed to report.

Years later, Mike believes his dad spurned pro football due to a knee injury and/or was needed to help his dad farm.

“I never really got the full story about that,” Mike said.

Building a family, fighting racism

Dick married Billie Jean, farmed, built houses, sold cars and for a couple of years was a wrestling promoter. His main trade was real estate.

After Dick and Billie Jean had son Richard (Eugene Richard Jr.) and a daughter Valarie, Billie Jean got very sick. Doctors struggled to diagnose what was wrong.

Dick hired Ella B. Smoots to take care of Richard and Valarie and took his wife to Denver. After doctors in Colorado could not come up with a solution, the Standefers returned to Plainview, where Dr. Eugene McCarthy figured out Billie Jean had a thyroid problem and got her healthy again.

More than a decade later, Ella B’s son Norman was killed in Vietnam in 1969.

“She called my dad and told him they would not let Norman be buried in the new cemetery in Plainview,” Mike said.

The Smoots were African American and segregation in Texas was barely in the state’s past.

“My dad told (her) he’d take care of it. He was very calm all the time,” Mike said.

Norman was buried in the cemetery.

Dick told a man at the cemetery, “Somebody is going to buried in the new cemetery tomorrow. It can be you or Norman Smoots,” Dick’s son Richard recalled. Dick was especially incensed anyone would disrespect a solider killed in action.

Mike added, “Dad felt people should be judged by their character, not their color.”

Dick also picked the first two African-American kids to play on a Plainview Babe Ruth League team – one was Norman Smoots.

“Norman was such a good athlete and could catch the ball so well, my dad moved my brother Richard to right field after earlier promising Richard he could play first base,” Mike said.

‘Dad didn’t like A&M’

Dick was passionate about Tech football.

If he wasn’t at a Red Raider game, he’d listen to Jack Dale on the radio.

“He would go out of the house so nobody could bother him and I would follow him,” Mike said. “He had a ’61 Pontiac and he’d turn on Jack Dale and we listened. If the quarterback fumbled, he would get the wrath of dad.”

Mike caught his dad’s wrath at a Tech game for cussing.

“I was five years old at the time and Donny Anderson was playing. I said, ‘I wish that woman would move her — so I could see Donny Anderson’ and boy, I really got a talking to,” Mike said.

Mike was asked if Dick ever mentioned having a favorite game when he played more than 75 years ago.

Dick never mentioned a favorite game, but Mike believes it had to be the 1946 A&M game.

“Dad didn’t like A&M. He thought they were arrogant – like they thought they couldn’t be beat and he was proud of that victory,” Mike said.

Another war story – and lesson

Growing up in Plainview, Mike found his dad’s Eisenhower-style uniform jacket with the brass U.S. buttons on the lapel, 1st Sgt. insignia on the sleeve and a box of pictures.

He begged his dad to tell him anything about his time in the Army.

“I don’t wanna talk about it,” Dick answered, looking at the television.

One of the photos had Dick and three other men standing in front of a bullet-riddled, GMC 2.5-ton truck.

Mike asked his dad about the photo and Dick decided to tell his youngest son the story – and lesson – behind the photo.

Dick and some of his buddies were on a road when they heard a German plane coming. The men took cover as the plane fired. The Americans walked back onto the road but scrambled for cover when the plane returned.

The Americans decided to return fire. The truck had a homemade sunroof and 50-caliber gun mount to shoot attacking planes.

The guys talked Dick into making a run for the truck – complimenting his speed and telling him he was a good shot.

After the plane made another attack, Dick ran for the truck, armed the machine gun and got off a few rounds as it came around again. But the plane’s tail gunner opened fire, narrowly missing Dick.

The truck was riddled with bullet holes.

Dick finished the story and looked at Mike.

“Don’t let your buddies talk you into something bad – and don’t ever try to be a hero,” Mike remembers being told.

Mike: Tech football and a career in the skies

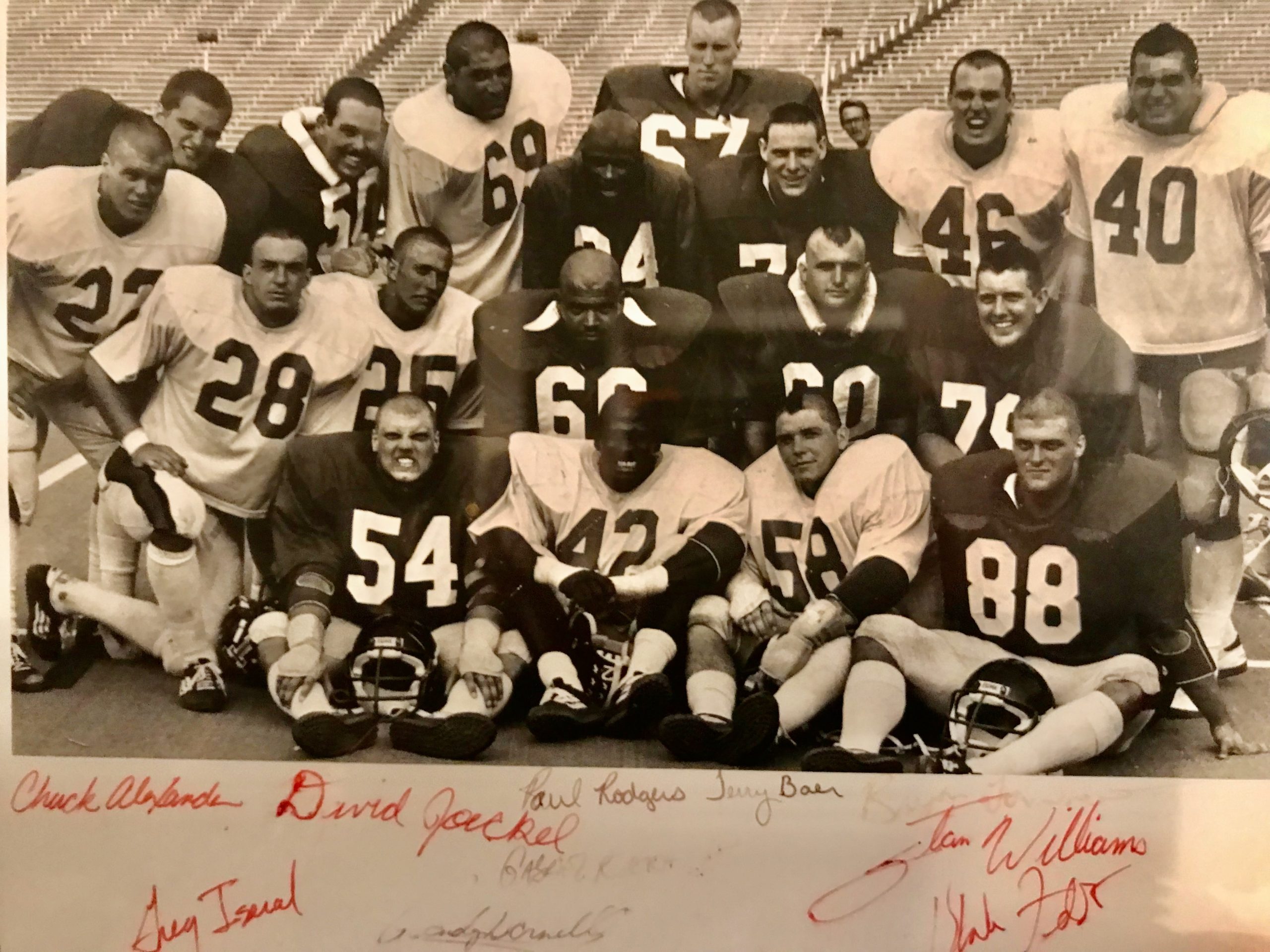

Mike wanted to play football at Tech and wear number 67.

“Because that’s what my dad did,” Mike said.

He had two years of eligibility when he made the team as a walk-on under Coach Rex Dockery in 1980. The next year he was put on scholarship by new coach Jerry Moore. Over his two years at Tech, the six-foot, five-inch Mike mostly played offensive line.

That season Moore told Mike he wanted him to be his first offensive graduate assistant the following year.

“I asked him, ‘What did I do?’” Mike remembers asking Moore.

“I wish I had 20 more guys like you on the team,” Mike said Moore told him. “That’s the biggest honor anyone had even given me.”

After his time as a grad assistant, Mike flew for the Navy, based in Hawaii.

“At the time we didn’t think about it much. You’re a young kid having fun, but it was pretty important. We kind of fought the Cold War. We had somebody airborne 24/7 365. All that sense of duty and doing the right thing was instilled into me by Dick Standefer,” Mike said.

Dick had his share of tragedy … and joy

Dick lost two brothers in a car accident and a beloved niece in a horseback riding accident, all in 1969.

He died at age 61 from brain cancer 15 years later.

Dick came out of his bedroom one day holding his shoes and wearing no socks, saying he was ready to go. His wife said, “You’re not wearing any socks.” Dick said, “Where are my socks?” That scared Billie and they went to the doctor. A malignant brain tumor was found. He died six months later.

“I was sitting there holding his hand when he passed. His body was strong as an ox and he fought for his last breath. He was just not coherent,” Mike said.

Dick also had his share of blessings.

He lived long enough to meet the first two of his six grandchildren.

Mike remembers a happy moment when Dick was holding and bouncing granddaugher Abby on his knee, tickling his next generation.

Dick was laughing – fully involved with the infant.

Mike looked at his dad and saw a youthful innocence on Dick’s face much like that of the young man on the bridge of the warship just off Utah Beach.