Double Mountain Fork of the Brazos River, image from City of Lubbock

As Texas continues to grow, the challenge of finding enough water to support the growth continues.

In West Texas, the challenge is harder because of decades-long dependence on groundwater – mostly the massive Ogallala Aquifer – getting sucked dry in spots.

For example, a few homeowners to the south of Lubbock in New Home told LubbockLights.com recently about not having enough water to take a shower.

The Texas Water Development Board met in Lubbock last week to discuss challenges and solutions.

Among the solutions:

- The Texas Water Fund helping replace leaky water systems which lose serious amounts of water.

- Lubbock’s ongoing switch from groundwater to lakes – including the upcoming Lake 7.

- Finding ways to reuse water coming from oil and gas production – something Texas Tech is involved with.

- Solutions come with a price tag.

“I just think the future of water is going to be more expensive. It just has to be,” said State Sen. Charles Perry (R), Lubbock, who sponsored the voter-approved Prop. 6 on last November’s ballot, creating the $1 billion Texas Water Fund.

Fixing leaky pipes

There are 8,000 municipal water systems in Texas and 70 percent are older than their useful life. Perry called it the “leaky pipes” problem during last week’s meeting.

“We lose an estimated 100 billion gallons of water a year. Most cities’ tax bases … do not keep up with the cost of these major infrastructure problems. The state is going to step into that role,” Perry said.

Details still need to be worked out, he added. More legislation is on the way, but a lot of money was already added to existing programs.

New water sources

There’s a bigger source of water, Perry said and this is where Texas Tech takes the lead.

Texas pumps 800 billion gallons of water out of the ground every year as part of oil and gas production. It’s called “produced water,” which is just a fancy term for water produced by the petroleum industry because it’s in the same underground formation as oil and gas.

Often, it’s too salty to drink. The solution is to pump it right back into the ground.

Tech just wrapped up a request for companies to submit proposals on putting produced water to good use. Companies build their own systems to treat water to a high enough standard for irrigating crops. Tech then provides analytical support.

Andrew Parks, a staff member for Perry, said, Tech received six proposals, “… several of which are very promising.” Tech is in contract negotiations with two and others might also be considered, he said.

The Legislature last year set aside $5 million for Texas Tech to experiment with methods for getting produced water cleaned up enough for industrial, commercial or agricultural use.

In addition to current groundwater, Perry said the state sits on 3.2 million acre feet of salty underground water. That’s more than a quadrillion gallons. (Think of a one followed by 15 zeros.)

It’s been done before

While the water board was in Lubbock, Doug White, the executive vice president of NGL Water Solutions, made a brief presentation. The parent company NGL Energy Partners, provides products and services to oil companies including water recycling or disposal.

In 2008, NGL built a recycle and discharge facility in Wyoming – good enough that the water was safe to drink, White said. A “similar technique” was tested already with water in the Delaware Basin (which covers parts of West Texas and Southeast New Mexico).

“The results of treated water were better than Denver, Colorado’s municipal drinking water,” White said.

The next step is to do a test run in Orla, Texas with nearly 17,000 gallons per day for 100 days – starting in May. The water will be used on irrigated crops.

Results will be shared with the public, White said.

According to him, petroleum companies in the Permian Basin generate 18 million barrels (more than 750 million gallons) of produced water every day.

Lake 7

Jarrett Atkinson, Lubbock’s city manager, told the meeting, “We are the hub city of West Texas. This is the region that is most heavily reliant upon groundwater.”

But there’s a huge shift to lake water – which preserves the groundwater for any future emergencies, he said.

“Lake Alan Henry has allowed us to cut our groundwater usage from our historical well field in half. And we will continue to slow that down,” Atkinson said.

Lubbock cut its groundwater use in half, Atkinson said and the city provides Wolfforth with 500,000 gallons a day, reducing its need for water wells.

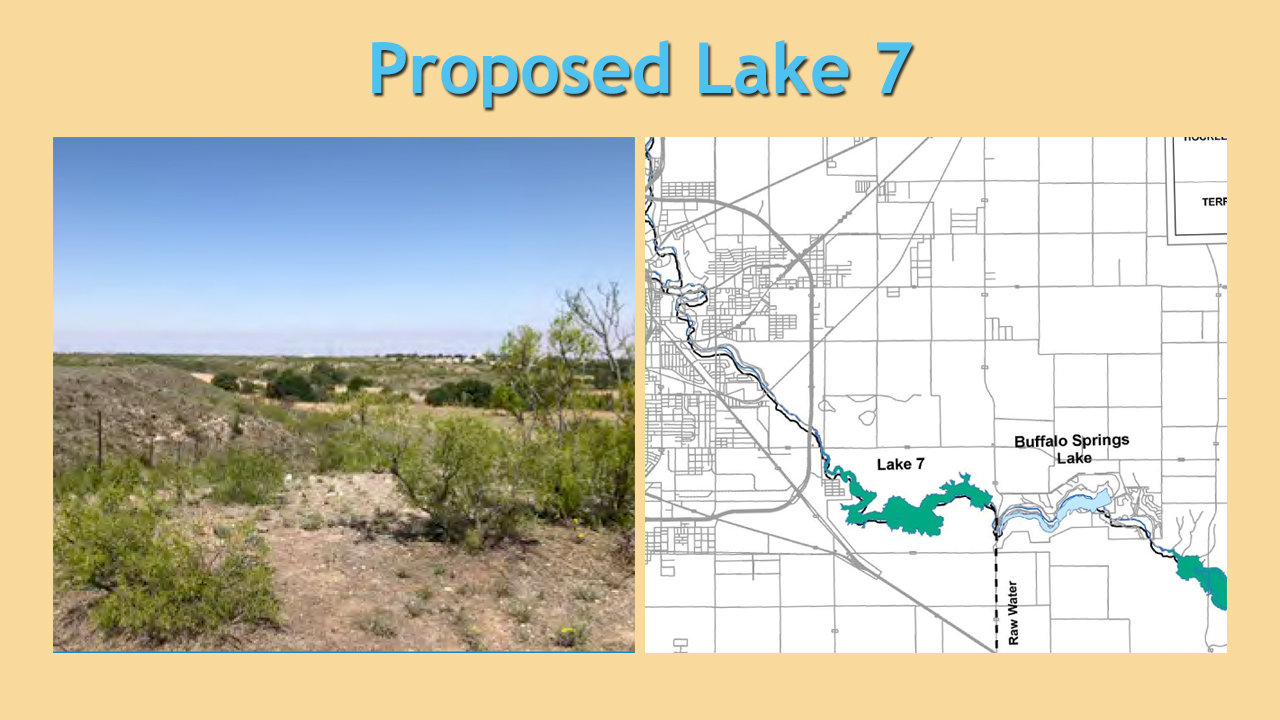

This week, if everything stays on schedule, state regulators will announce the approval of a permit for Lubbock’s Lake 7. Lubbock still needs a federal permit so there’s work to be done.

Lake 7 goes between East Loop 289 and Buffalo Springs Lake. The cost is estimated between $205 million and $300 million. It will provide an estimated 10 million gallons per day. The lake will collect Lubbock’s rainwater from three different drainage systems. It will also collect used water from the future Leprino cheese plant in Northeast Lubbock.

Construction starts in the early 2030s.

There are plans for a trail and recreational areas along the north shore on property the city already owns.

There’s a cost

The $1 billion in the Texas Water Fund makes a big difference. But water is not going to be cheap in the future.

“Anybody who is reliant on groundwater in this part of the world that does not believe the cost of water will increase is probably not being realistic,” said Randy Criswell, Wolfforth city manager.

“We’re basically completely relying on groundwater, which is not going to be here forever,” Criswell said. Cities near the Texas coast can use marine desalination, to treat water from the Gulf of Mexico. But for Wolfforth, the only source, except for a contract with Lubbock, is the Ogallala Aquifer.

The water is not particularly deep, Criswell said – meaning the underground water layer is only 200-300 feet thick. Wolfforth drilled an experimental water well a few years ago looking for deeper water in the Dockum Aquifer.

“That well was no good,” Criswell said.

Wolfforth announced a 25-year water contract with Lubbock. Lubbock will increase its supply to Wolfforth from 500,000 to 750,000 gallons in June 2026. (Wolfforth pays one-and-a half times Lubbock’s wholesale rate.)

Up until now, no one paid for water itself but just the pipes and treatment plans. It was a “cheap commodity,” said Perry.

How much cost? Perry does not know yet. It will vary from city to city, and he hopes to have a map of proposed water treatment plants and pipelines during the 2025 legislative session.

Comment, react or share on our Facebook page.

Coming soon, we will offer a weekly newsletter to highlight our work. Use the form below so you don’t miss a thing.

Facebook

Facebook